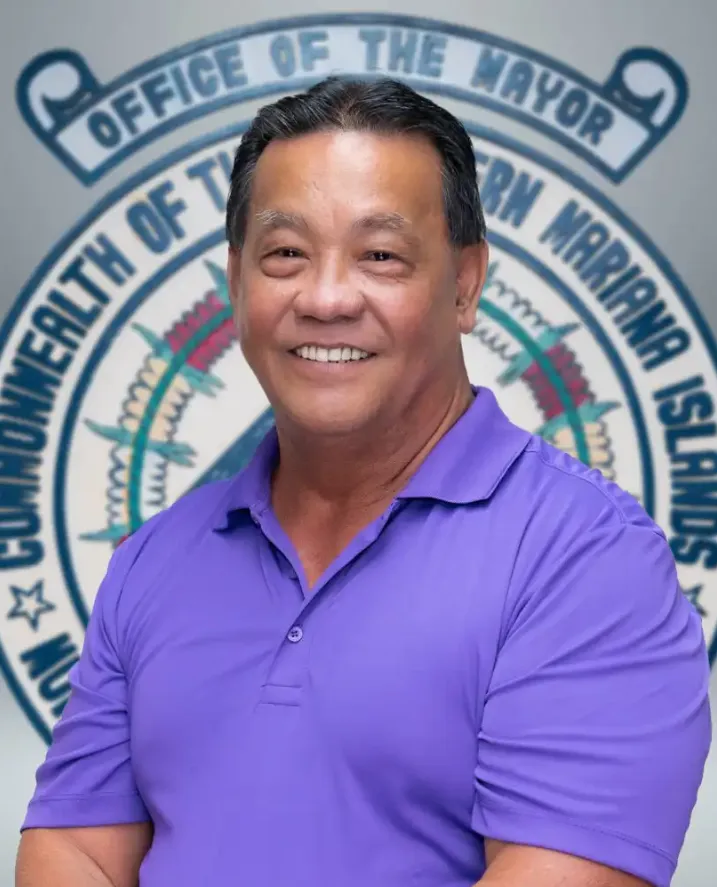

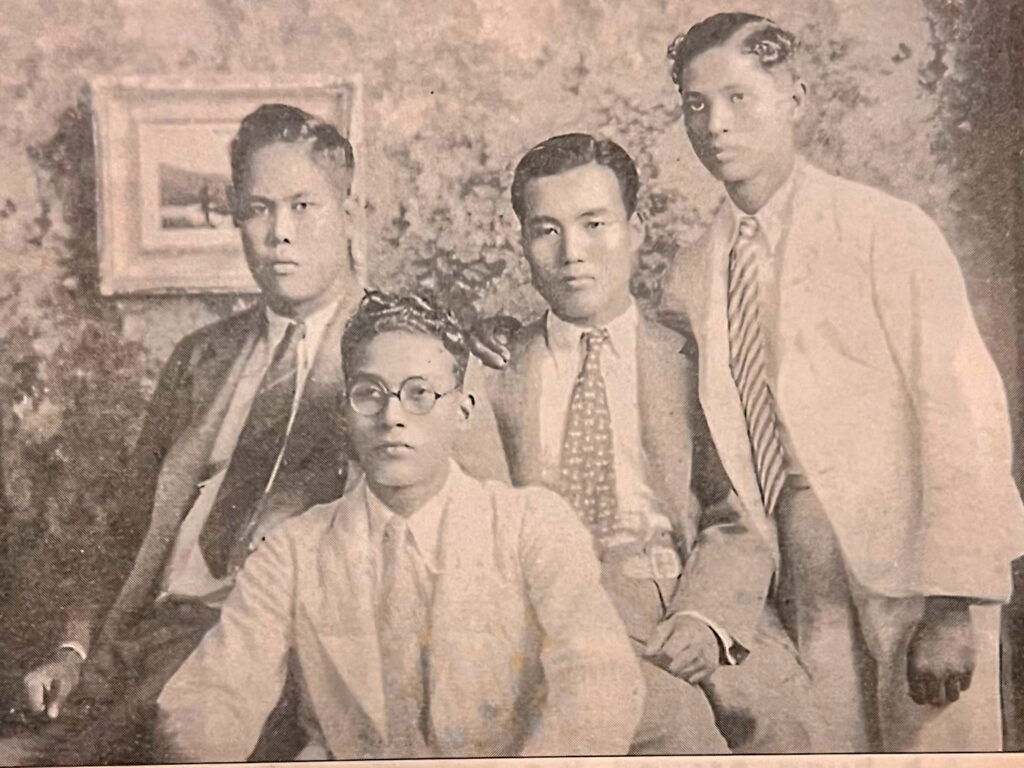

Taken on August 1934 in Tokyo, Japan. This is a photo of the young Herman Jose, standing right, along with Saipan residents, from left, Antonio Diaz, Francis Diaz, and Naoki. Herman Jose R. Guerrero was employed at Nakamura Store and was sent to Japan for training.

The Northern Marianas was part of the Japanese-governed League of Nations-created South Seas Mandate. Japanese rule in the Northern Marianas began in October 1914 when they took possession of the rest of Micronesia. Japan’s authority was based on several secret agreements with the British designed to keep the peace in Asia in the event of war.

After World War I, Japan received the islands by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, and then later as a mandate under the League of Nations on December 17, 1920.

The Japanese settlers played a crucial role in advancing the local workforce in the Northern Marianas, along with the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, and the Marshal Islands. As part of the League of Nations, they were sent as contract workers or have established businesses.

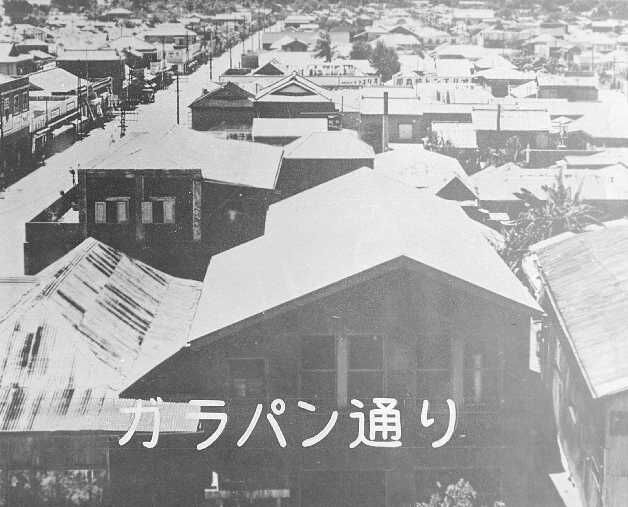

There was one Japanese bakery that was established at the heart of Garapan, the principal area for business during the Japanese government on Saipan. According to a pre-Second World War Japanese map, Garapan was divided into four area: Garapan 1, Garapan 2, Garapan 3, and Garapan 4.

Japanese rule was direct: islanders were given little part in local government. These included how basic laws were extended to the islands with only a few modifications to meet local conditions. Formal educational facilities were restricted, with emphasis placed on learning the Japanese language.

Public health conditions, however, were improved, and hospitals were established.

Economic development was Japan’s main interest, and large sugarcane plantations and refineries were started on Saipan and Rota. Large numbers of laborers and investment capital were made available. There was also full employment.

During this period, there was a large Japanese civilian population estimated to be about 20,000 at that time, in addition to the 4,000 Chamorros on the islands.

Shimada Bakery was one of the hundreds of Japanese businesses that was in operation.

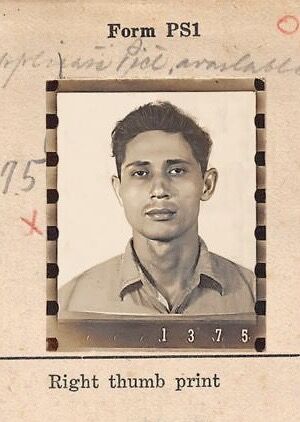

The young Herman Jose photo as a policeman under the Japanese administration.

In the Japanese-run government of Saipan, and as fate would have it, the young Herman Jose was only 21 years old when he was fortunate to be handpicked and enrolled to intern at Shimada Shoten (bakery) Matsumuto Coffee Shop in Garapan.

He picked up his baking skills quickly.

Prior to that, Herman gained his first experience working as a store assistant for a Japanese retailer called Nakamura during the Japanese occupation. Garapan was home to the Shimada Bakery and the Nakamura Store. The young Herman Jose would eventually learn how to bake at the Shimada bakery.

His extraordinary role and influence on the lives of civilians, Carolinians, and Chamorros started in the closing stages of World War II during which a food shortage was ravaging Saipan. The island was the last stronghold of the Japanese Imperial Forces in the Pacific.

“My father started as an apprentice, basically learning the trade of the bakery before the war. The Japanese bakery was known at that time as having very good bakers,” said Jesus Tenorio Deleon Guerrero, better known as Jesus Pan, the second oldest child.

A photo of a Garapan (Galapang), Saipan during the Japanese-administration of Micronesia.

The young Guerrero left Shimada’s Bakery and worked as a police and intelligence officer for the Japanese government, becoming a Japanese policeman at the age of 28.

Jesus Pan recalls his father sharing with him why he became a policeman during the Japanese occupation of Saipan. His father was one of the few locals who worked for the Japanese police force in Saipan at the time, according to Jesus, because of his fluency in the Japanese language (Nihongo). “I think the reason my father joined the police force during the Japanese occupation is that he was fluent in both spoken and old Japanese.”

The young Herman was dispatched to the northern island of Pagan, another son, JuanPan, recalling the story told by his father. “As a police officer for the Japanese government, he was there to take care of the people,” JuanPan said.

Herman, as a young policeman, according to the Japanese government of Saipan’s official record, had a registered residential address at #158, 3rd Street, North Garapan.” He was paid at a monthly rate of 63 yen.

The Japanese colonial government in Saipan allowed for residents to hold government positions of supervisory authorities over communities of islanders. Throughout most of Micronesia, various chiefs had prevailed over indigenous systems of maintaining social order. This set up was the model used by the Germans, which was designed to cause the least disruption.

In addition to officials in the government, islanders served in the police forces. The islanders who served as patrolmen were considered the backbone of the local administration because they were often the only point of contact between Japanese settlers and the islanders.

To be eligible to work as a patrolman, one had to be under forty years of age, complete five years of public school, and been in good health. At the start of their employment, patrolmen were trained for three months in Japanese language and methods of law enforcement. Islander patrolmen were supposed to assist Japanese policemen, and had a wide range of responsibilities.

Their duties exceeded those that would normally be expected from a policeman in Japan: they collected taxes, enforced sanitary regulations, disseminated public information, supervised road building, selected local students who would be given the limited number of slots in public schools, and generally served as intermediaries between the government and local communities.