The following is the text of the author’s remarks during the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Saipan at American Memorial Park on June 15, 2024.

FIRST, of course, my congratulations to the Honorable Mayor of Saipan, RB Camacho, along with my Chamolinian brother Gordon Marciano and the ever-effervescent Gary Sword, founder of KKMP Radio. You and your team have done an excellent job of organizing this truly historic event.

My remarks are very short today. I only want to answer one question. “Who do we have to thank for these “80 years of Peace in the Pacific?”

I needn’t detail the battle for Saipan here. The bottom line is that although the Japanese soldiers and sailors on Saipan did their best to defend their “Little Waikiki” in the Marianas, the island fell to American forces on July 9, 1944. The Japanese leadership in Tokyo recognized that the loss of Saipan meant that B-29 bases would soon be built in the Marianas and shortly after than bombs would start falling on the Japanese Home Islands. Hideki Tojo, War Minister and Prime Minister of Japan at the time, the man most responsible for pushing Japan into war against the United States, was forced to resign along with his war cabinet. At that moment, Emperor Hirohito had an opportunity to end the war and save hundreds of thousands of Japanese lives, but did not.

Admiral Ernest J. King, Commander-in-Chief, US Fleet, and General Henry “Hap” Arnold, commander of the 20th Air Force and all B-29 operations, firmly believed that Japan could be forced to surrender through strategic bombardment and blockade before a bloody invasion of the Japanese Home Islands became necessary. On the other hand, General George Marshall, commander of all U.S. Army forces, was convinced that as with Germany, U.S. armed forces would have to march into Tokyo and capture the Imperial Palace in order to force unconditional surrender.

President Harry S. Truman took office on April 12, 1945, upon the death of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Truman had never been involved in the Manhattan Project and was not aware of the atomic bombs. General Leslie Groves, Army Corps of Engineers, commander of the Manhattan Project, told Truman about the new plutonium-based bomb. If it worked, then the U.S. could manufacture an endless supply of atom bombs. The plutonium bomb mechanism was so new however, it would have to be tested. Eventually, the test was scheduled for July 16.

After Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, Russian Generalissimo Joseph Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill wanted Truman to come to Germany and help draft the treaty ending the war in Europe. But before meeting with Stalin, Truman wanted to know if the new bomb worked. He agreed to a meeting with Stalin and Churchill in Potsdam, German, just outside Berlin, and arrived there on July 15, 1945.

The plutonium bomb was tested in the desert of Alamogordo, New Mexico on July 16 and word was immediately passed to Truman that it had worked quite well. With this new weapon up his sleeve, Truman was ready to play poker with Stalin over the issue of self-determination for conquered people. Churchill had already warned Truman that the Russians were stealing everything of any value from the lands they had captured from Germany at taking them home to rebuild mother Russia, leaving behind Communist advisors. Germany, itself, was being torn into four pieces. Truman did not like what he saw, but could do nothing about it.

On August 6, flying from Tinian and according to plan, the uranium-based bomb nicknamed Little Boy was dropped on Hiroshima and worked. At daybreak on August 8, Stalin sent his Red Army across the border into Manchuria, China, hurriedly joining the war against Japan in an effort to gain some spoils from the Pacific War. Within days they reached a point from which they could para-drop Russian soldiers into Hokkaido, the northern-most of Japan’s home islands.

With no surrender offer, the first plutonium-based bomb, nick-named Fat Man, was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, and it worked. Early in the morning of August 10, the Japanese made their first offer to surrender. With a slight modification allowing for the maintenance of the imperial system, Emperor Hirohito accepted “unconditional surrender” and announced his decision directly to the people of Japan on August 15. Truman immediately announced America’s acceptance, before Stalin could drop any troops into Hokkaido.

After having watched how Stalin was tearing apart Germany and reorganizing Europe to his own advantage, Truman decided that Japan would not be divided — it must remain unified.

Stalin wrote to Truman on August 16: “I have received your message with the ‘General Order No. 1.’ Principally I have no objections against the content of the order. However, … The Russian public opinion would be seriously offended if the Russian troops would not have an occupation region in some part of the Japanese proper territory.”

Truman thought it over, figured out how to say “No!” as politely as possible, then responded on August 18: “Regarding your suggestion as to the surrender of Japanese forces on the Island Hokkaido to Soviet forces, it is my intention and arrangements have been made for the surrender of Japanese forces on all the islands of Japan proper, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku and Kyushu, to General MacArthur.”

Stalin did not press the issue at that time for two reasons: 1. Truman had the bomb, and 2. He was more concerned about getting all he wanted from Europe — at the time.

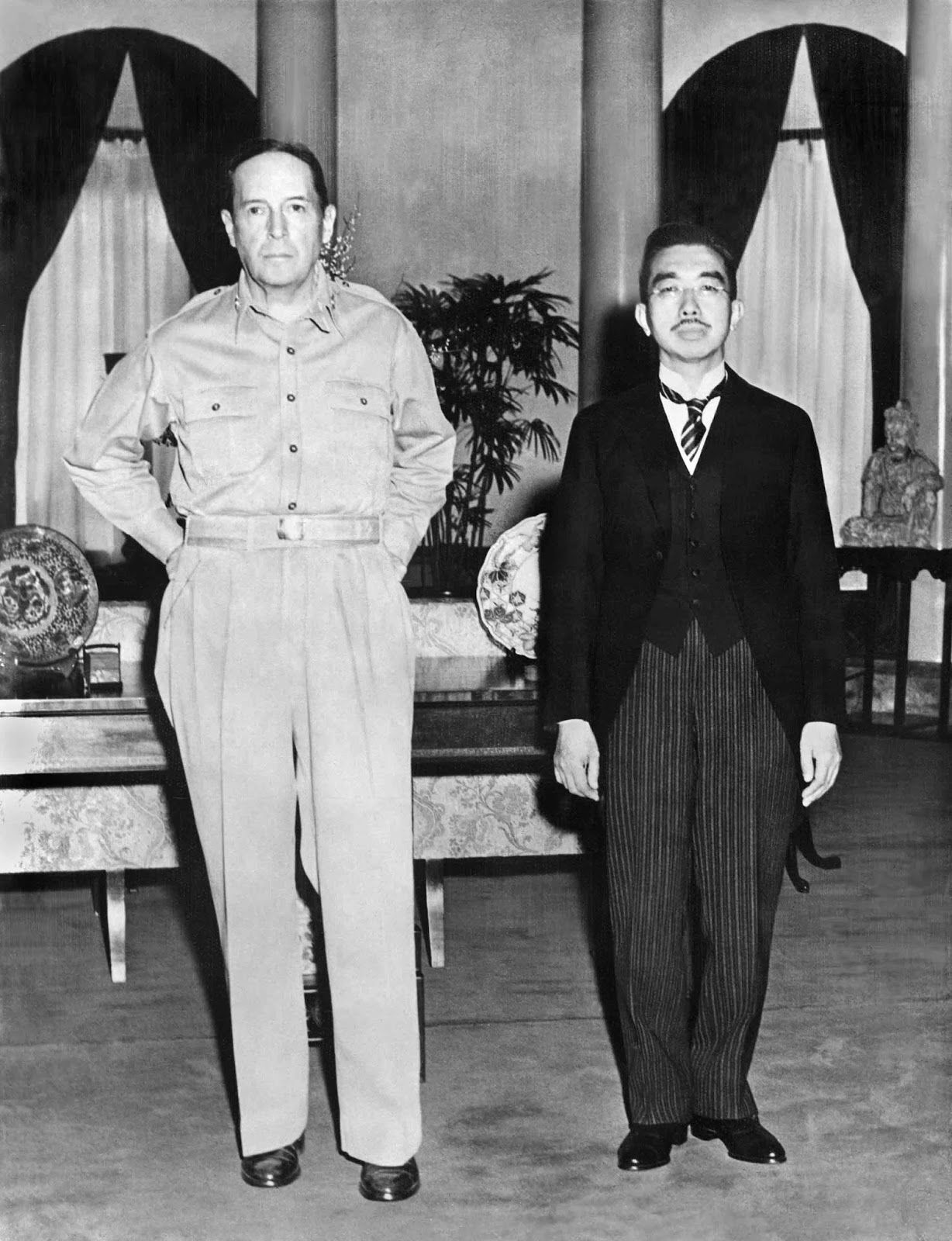

Equally important, Emperor Hirohito accepted the defeat on behalf of the people of Japan. As ordered, he reported to General MacArthur’s headquarters on September 27. There, he stepped away from his role as emperor, took of his top hat and stood before MacArthur as a bare-headed subordinate and offered to work cooperatively at rebuilding Japan, which won the General’s favor.

Similarly, the emperor-like General MacArthur, stepped up from his military role to become America’s number one diplomat in Japan. Both great leaders recognized they could accomplish more by working together at reconstructing Japan, both physically and politically.

To summarize, because President Truman had stood strong for maintaining a unified Japan, and because Hirohito and MacArthur stepped up to the task, a new Japan emerged from the occupation years. In 1951, alongside the Treaty of San Francisco, formally ending World War II, the U.S. and Japan signed a Mutual Security Treaty. With some modifications, that treaty between Japan and the United States stands stronger today than it has ever been.

Today, we are so blessed to be joined by such a wide variety of military and civilian leaders coming together on Saipan to jointly commemorate “80 years of Peace in the Pacific.” I only hope, a similar, if not bigger, celebration will take place right here 20 years from now — A Century of Peace in the Pacific. That has a good ring to it, don’t you agree?

Thank you, all, very much.

President Harry Truman announces the surrender of Japan.

Gen. Douglas MacArthur with Emperor Hirohito.