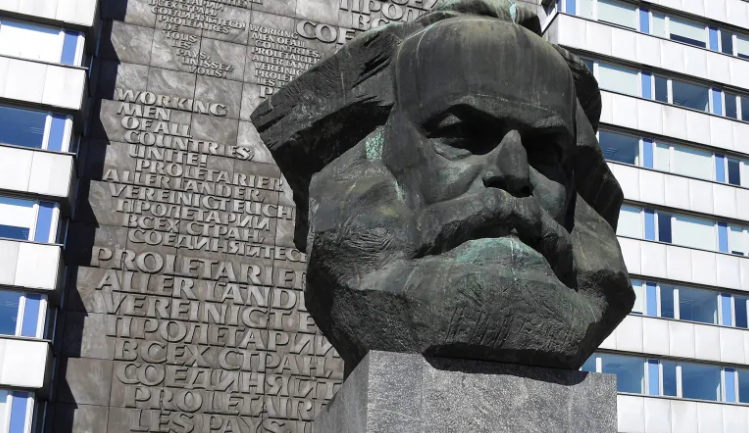

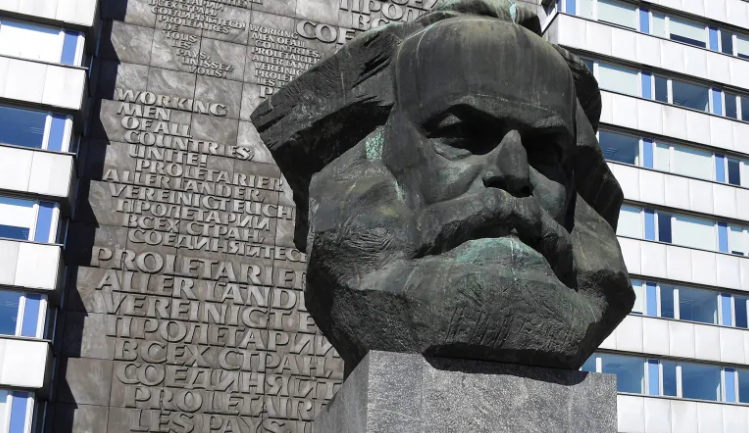

Karl Marx monument in Chemnitz, Germany.

JON Miltimore of the libertarian Foundation for Economic Education has noted that many of those who want to “fix the world” can’t fix themselves. Like many sagacious observations, this is not a new “finding.” About 375 years before the birth of Christ, Plato advised a self-appointed savior of the world to set his own house “in good order” by “harmonizing the various parts of his soul — before he can ensure justice in his actions toward others.” In other words, those who want to govern others should govern themselves first.

Miltimore cited Karl Marx as a primary example of a well-intentioned, highly intelligent person who believed that he had found the solution to the world’s socio-economic problems. And yet, Miltimore added, “it’s hard to imagine a more wretched human being than Karl Marx. It was almost as if all of the worst traits of humanity were bundled into this one spiteful man, who then constructed a philosophy based on his own bitterness and self-loathing.”

The champion of workers and the advocate for equality, Marx “was lazy but greedy, always begging for money from family and friends who feared for his happiness and sanity…. He was so self-centered…. His lechery and drunkenness are well chronicled.”

Not surprisingly, he was a total slob.

“Here is how he was described in a Prussian police report circa 1850:

“ ‘Washing, grooming, and changing his linens are things he does rarely, and he likes to get drunk…He has no fixed times for going to sleep or waking up….everything is broken down… . In a word, everything is topsy-turvy. To sit down becomes a thoroughly dangerous business.”

His home was “filthy, disordered, and disheveled….” Marx himself “stunk badly and suffered from boils head to toe, including on his genitals.” The historian Paul Johnson said Marx was usually angry. “[L]ying perhaps at the very roots of his hatred for the capitalist system was his grotesque incompetence in handling money.” He and his unfortunate family would not have survived without the generosity of his well-off (son of a capitalist) friend and “co-founder of Scientific Socialism,” Friedrich Engels.

Marx envisioned a “massive change” in human nature through a “science-based” “universal” system that would, once and for all, establish a humane, just, equitable and prosperous world.

But, Miltimore said, Marx “could not even manage his own home. His own health. His own life.” Which is, to be sure, a hard thing to do — for anyone.

“Sometimes,” Miltimore said, “it feels as if there are 1,000 hurdles in front of us that prevent us from living the life we want, and twice as many pitfalls.” Now imagine being a parent and managing a household — or a small business. These roles involve hard and often frustrating tasks and pressing obligations. Yet some of them believe that because of their education, intelligence and good intentions they can devise policies that, once implemented, will improve the lives of other people.

As the philosopher Herbert Spencer once put it:

“Home-experiences daily supply proofs that the conduct of human beings baulks calculation. Yet, difficult as he finds it to deal with humanity in detail, he is confident of his ability to deal with embodied humanity. Citizens, not one-thousandth of whom he knows, not one-hundredth of whom he ever saw, and the great mass of whom belong to classes having habits and modes of thought of which he has but dim notions, he feels sure will act in ways he foresees, and fulfil ends he wishes.”

In contrast, Spencer said, a “cautious thinker may reason: — ‘If in these personal affairs, where all the conditions of the case were known to me, I have so often miscalculated, how much oftener shall I miscalculate in political affairs, where the conditions are too numerous, too widespread, too complex, too obscure to be understood…. When I remember how many of my private schemes have miscarried; how speculations have failed….; how the thing I desperately strove against as a misfortune did me immense good; how while the objects I ardently pursued brought me little happiness when gained, most of my pleasures have come from unexpected sources; when I recall these and hosts of like facts, I am struck with the incompetence of my intellect to prescribe for society.”

People with such a high level of self-awareness aren’t usually the same individuals who believe they can “make a difference” by seeking and assuming elective office. The “solution,” many of us insist, is to elect “good” if not “virtuous” candidates, and “throw the rascals out” at the next election. However, as the economist and historian Robert Higgs would put it, “Here in the United States we have been flinging rascals hither and yon for more than two centuries. But what do we have to show for it?”

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com