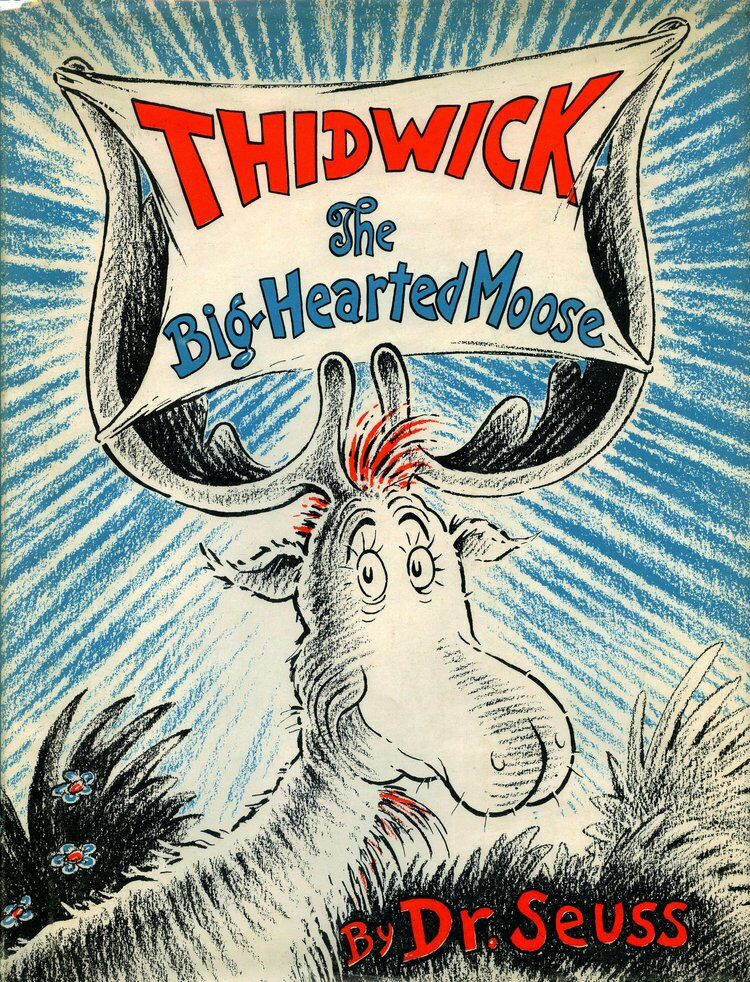

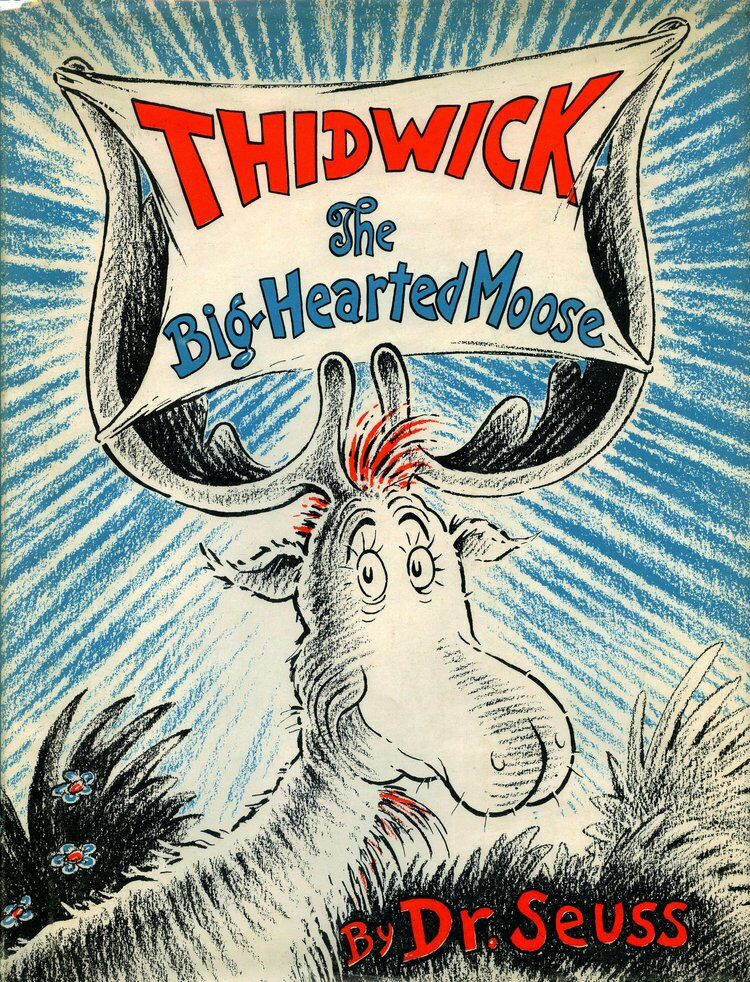

DR. Seuss, the author of “The Lorax,” an anti-greed screed, also wrote “Thidwick, the Big-Hearted Moose.” In a recent American Institute for Economic Research article, economics teacher Bruce Rottman said Thidwich is about the politics of niceness and its perils. This, in turn, reminded me of the following quotation usually attributed to Alexander Fraser Tytler or Alexis de Tocqueville:

“A democracy will continue to exist up until the time that voters discover that they can vote themselves generous gifts from the public treasury. From that moment on, the majority always votes for the candidates who promise the most benefits from the public treasury, with the result that every democracy will finally collapse due to loose fiscal policy, which is always followed by a dictatorship.”

In Dr. Suess’ tale, Thidwick is a happy moose with a heart of gold and a lot of friends. One day, one of them, Bingle Bug, approached Thidwick, and asked to ride on his horns for a way.

“There’s room to spare,” Thidwick said, smiling, “and I’m happy to share.”

The grateful bug then invited a Tree Spider. “There’s plenty of room,” Bingle tells the spider, “and it’s free!”

“Then along comes a Zinn-a-zu bird, who gets married and makes his nest from moose hair, and his uncle, a Woodpecker, and then Herman the squirrel and his family, who lived in the holes Woodpecker drilled into Thidwick’s horns.

“Meanwhile, Thidwick’s moose friends leave him to search for more moose moss to munch, and as his stomach growls, he decides to join them in their swim to the south shore of Lake Winna-Bango.

“Not so fast. The animals vote, and Thidwick loses, 11 to 1. He stays, despite his increasing hunger and the increasingly weighty burdens on his horns.”

For Rottman, Thidwick is a good metaphor for democracy. “In a democracy,” Rottman said, “politicians vote for bills with obvious benefits to their constituents and uncertain, diffuse, and understated costs to taxpayers — who are often the same as their constituents, though clever cost shifting can cure that potential problem. As a result, the state grows into a Leviathan.”

In his highly informative book published in 2017, “The High Cost of Good Intentions,” John F. Cogan noted that American revolutionary war pensions were the nation’s first entitlement program, the laws for which were passed between 1789 and 1793. By 1818, a U.S. senator, Nathaniel Macon, was already complaining that although “pensions in all countries begin on a small scale, and are at first generally granted on proper consideration…, they increase till at last they are granted as often on whim or caprice as for proper considerations.” Along the way, Congress had “discovered the power of entitlements as an efficient vehicle for gaining electoral advantage.”

Today, Cogan wrote, “entitlements have become a complex system that…transfers hundreds of billions of dollars each month from one group in society to another, most often regardless of individual need. The scale of federal entitlement assistance today is unmatched in human history.”

And this was before Covid-19 and the trillions in federal pandemic dollars unleashed by well-meaning politicians.

As “well-meaning and beneficial as many entitlements may be,” Cogan said, “they have come at a high cost. They have undermined the natural human desire for self-sufficiency and self-improvement. Social Security and Medicare have reduced the perceived need by young workers to save for their retirement and have induced senior citizens to forgo years of productive and rewarding employment. The welfare system’s high marginal tax rates have discouraged work and penalized investments in human capital. The system has created incentives for young women to bear children out of wedlock and remain unmarried. It has discouraged fathers of young children from meeting their parental responsibilities. This high human cost has been matched by large fiscal costs and monumental inefficiency.”

Thidwick the big-hearted moose “solved” his problem by “giving his head a twist, flinging the free riders to the floor.” This time, they didn’t get to vote.

Like the occupants of Thidwick’s horns, the beneficiaries of government generosity in a democracy constitute the overwhelming majority of voters. They will vote against any candidate for office who dares threaten their government benefits and/or jobs.

So what is the “solution”?

Not a dictatorship, of course. History and current events clearly show that dictators don’t solve the problems created by democracy — they just make them so much worse while creating new ones.

Cogan believes that incremental changes ought to do the trick. He said the “system needs to be restructured to become a safety net that preserves the dignity of recipients and rewards self-reliance.” Moreover, he said, “providing assistance to individuals who are impoverished through no fault of their own is not only consistent with widely held public goals, it is a hallmark of a compassionate society.”

Cogan said “as entitlement costs continue to grow and their harmful consequences become more apparent, public pressure will grow and will ultimately force government to change policies.”

I wonder though.

Democracy, as Jonah Goldberg would put it, “doesn’t deliver permanent solutions or eternal social justice. It’s a hedge against tyranny and a way to settle differences without resorting to the sword. And that’s good enough.”

But it’s never good enough for most of us who believe that democracy is “a cure-all.” Hence, we also believe, to quote H.L. Mencken, that “any boil upon the body politic, however vast and raging, may be relieved by taking a vote; any flux of blood may be stopped by passing a law.”

Laws like the anti-littering act.

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com