HONOLULU, Hawai’i — The City of Las Vegas has such a large Native Hawaiian population that it is often referred to as the ninth island of Hawaii. Within this local diaspora, some Native Hawaiian leaders question whether the White House has set the right policy priorities for renewed American engagement with Pacific Island Countries.

Doreen Hall, president of the Las Vegas Hawaiian Civic Club, says that she would like to see the Biden Administration place more emphasis on indigenous rights in domestic and foreign policy. It is not enough to just reimagine the United States as a Pacific nation and make the pivot to Pacific regionalism. She argues that the United States government has “to go back in history” and face the fact that “our people are still fighting for basic rights.”

At the first-ever Pacific Island Country Summit, Hall believes that the Biden Administration missed the opportunity to elevate indigenous rights for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders on the world stage. “Time and again we have fought for indigenous rights,” she declares, but the summit “left it for the imagination. We have not won.”

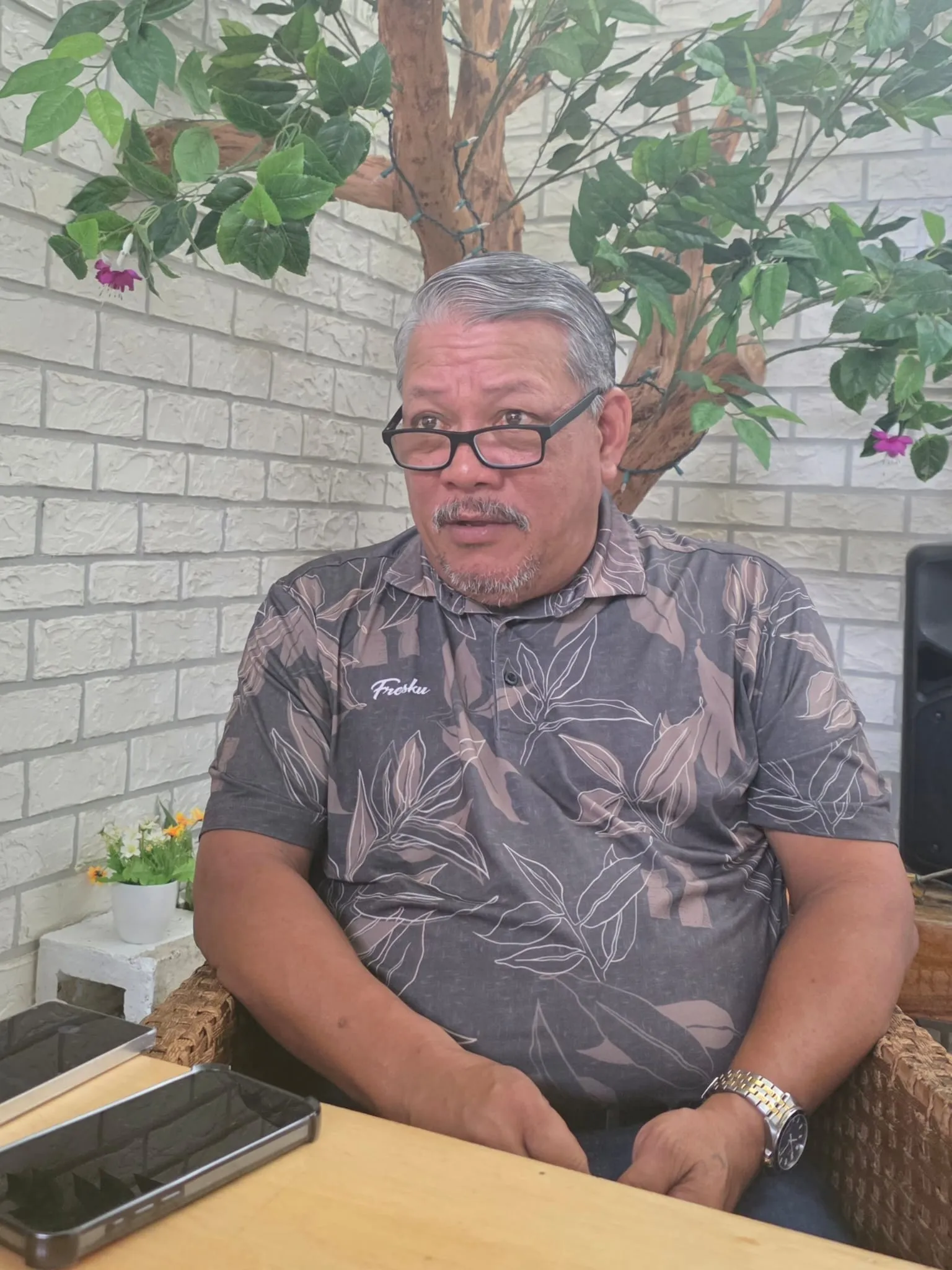

Vincent Souza shares these concerns. Reflecting on the eleven points outlined in the summit declaration, the Clark County AANHPI Community Commissioner says, “I would have wanted indigenous cultures to be number one.” However, he stresses, “I did not see a commitment made to preserving indigenous cultures.”

Hall and Souza suggest that the White House’s failure to make an explicit commitment to preserving indigenous cultures may indicate deeper seeded problems that still need to be brought to the surface.

“When it is not listed or masked,” Souza maintains that indigenous rights become nothing more than “a talking point,” which begs the question, “Who are you preserving these islands for?”

Here, it may be important to mark a distinction between being aware of the existence of cultural issues and understanding why those cultural issues exist in the first place.

While Souza admits that the “Biden Administration recognizes cultural issues,” he says that he doesn’t feel that senior officials have enough “knowledge of our cultures” to begin to understand “the other issues” that should have been tackled at the summit.

Hall advises the White House to start with knowledge about the languages of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders.

As Professor William “Pila” Wilson of the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo once said, the Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander languages represent more than just systems of communication. They are living repositories “of the history, culture, and worldview of a people.”

Dean Jonathan Osorio of Hawaiʻinuiākea School of Hawaiian Knowledge lectures that the Hawaiian language — the living repository of the history, culture, and worldview of the Native Hawaiian people — was “brutalized” by the United States government for much of the twentieth century.

Osorio traces this problem back to the “Americanization of the school system.” This was done by American policymakers who believed that “Hawaii could not be truly America” if Native Hawaiians continued to speak their own language in daily life, he says.

Soon after the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, a statewide ban was imposed on the use of the Hawaiian language as a medium of learning and teaching. Osorio says that this lasted for approximately eight decades.

This racial integration policy left scars in the collective memories of many Native Hawaiians. To protect their “children from punishment,” Osorio points out that Native Hawaiian elders often “decided to speak only English,” even within their own household.

While the Hawaiian language has experienced a revival in recent decades, Osorio observes that it has yet to totally recover: “The recovery has not been as rapid as we would have liked. It will take many more decades to bring it back into full practice. We are nowhere near where we need to be. We lag behind the Māori.”

Given what he calls the “abysmal history” of the United States government when it comes to “being tolerant of other languages,” Osorio is not surprised that the summit did not do more to highlight Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander languages. However, he suggests that the Biden Administration sacrificed a public diplomacy win in the process.

According to Osorio, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander languages should have been “front and center” at the summit. That not only “would have been a startling thing for anyone who follows these proceedings,” it would have shown that the United States government was serious about working through its “own colonial legacy.”

Hall strikes a more personal note. Not one for broad covering statements, she gets straight to the point: “when you took away our language, you took away who we are.” Now, she thinks that it is time to “give us some opportunity to regain our control” by engaging with Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in “our language.”

The Biden Administration may want to look to the Hawaiian Kingdom for inspiration.

Osorio claims that the Hawaiian Kingdom “was truly a multilingual nation.” Although “Hawaiian was the language of national discourse,” he notes, “other languages were also honored.” As evidence, he recalls how the Court employed staff to translate official documents into English, Chinese, and Japanese.

Osorio thinks that the United States government should have followed the monarchy’s lead and translated the key summit deliverables into the major indigenous languages of the Pacific Islands Region before releasing them.

While this “would not be an easy nor inexpensive thing to do,” Osorio counters that no one has the right to “ask Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders a question about practicality. Why is that our problem? If you don’t do things like that, then how do you expect languages that have been brutalized to come back?”

If more of an effort had been made to engage Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders in their own languages, Osorio believes that more indigenous people would have known about the summit. In his words, such a move would have “significantly” increased awareness in Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities across the United States.

Michael Walsh is a freelance foreign correspondent who formerly served as the Washington Correspondent for The Diplomat.

President Joe Biden speaks during the first U.S.-Pacific Island Country Summit at the State Department in Washington, Sept. 29, 2022. Secretary of State Antony Blinken listens at left.