SINCE the Feb. 7, 2018 publication of Junhan B. Todiño’s Marianas Variety story, “Group to build Amelia Earhart monument on Saipan,” much has been written in Variety and on my blog, Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last, about Marie Castro and the original Saipan eyewitnesses to the presence and deaths of Earhart and Fred Noonan on Saipan in the days and months following their July 2, 1937 disappearance during their attempted world flight.

The Variety stories can still be found on my blog. A few of the most prominent of these include my April 2, 2018 post, “Marie Castro: Iron link to Saipan’s forgotten history”; Oct. 16, 2018, “Josephine Blanco Akiyama returns to Saipan”; and May 18, 2018, “Marie Castro, a treasure chest of Saipan history, Reveals previously unpublished witness accounts.”

When it comes to Earhart and Noonan on Saipan, we have another, entirely separate classification of witnesses and eyewitnesses: the American GIs who were on Saipan in the summer of 1944. The Battle of Saipan, fought from June 15 to July 9, 1944, was the most important battle of the Pacific War to date. The U.S. 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions, and the Army’s 27th Infantry Division, commanded by Lt. Gen. Holland Smith, defeated the 43rd Infantry Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, commanded by Lt. Gen. Yoshitsugu Saito.

The loss of Saipan, with the death of at least 29,000 Japanese troops and heavy civilian casualties, precipitated the resignation of Japanese Prime Minister Hideki Tojo and left the Japanese mainland within the range of Allied B-29 bombers. Saipan would become the launching point for retaking other islands in the Mariana chain, and the eventual invasion of the Philippines, in October 1944.

The victory at Saipan was also important for quite another reason, one you will not see in any of the official histories. At an unknown date soon after coming ashore on D-Day, June 15, American forces discovered Amelia Earhart’s Electra 10E, NR 16020, in a Japanese hangar at As Lito Field, the Japanese airstrip on Saipan.

Thomas E. Devine, author of the 1987 classic, “Eyewitness: The Amelia Earhart Incident,” was a sergeant in the Army’s 244th Postal Unit, and came ashore at Saipan on July 6, just a few days before the island was declared secure. Devine was ordered to drive his commanding officer, Lt. Fritz Liebig, to As Lito Field, and there he was soon informed that Amelia Earhart’s airplane had been discovered, relatively intact.

Devine later claimed he saw the Electra three times soon thereafter — in flight, on the ground when he inspected it at the off- limits airfield, and later that night in flames.

During that period, Marine Pvt. Robert E. Wallack found Amelia’s briefcase in a blown safe in a Japanese administration building on Saipan. “We entered what may have been a Japanese government building, picking up souvenirs strewn about,” Wallack wrote in a notarized statement. “Under the rubble was a locked safe. One of our group was a demolition man who promptly applied some gel to blow it open. We thought at the time, that we would all become Japanese millionaires. After the smoke cleared I grabbed a brown leather attaché case with a large handle and flip lock.”

The contents were official-looking papers, all concerning Amelia Earhart: maps, permits and reports apparently pertaining to her around-the world flight. “I wanted to retain this as a souvenir,” Wallack continued, “but my Marine buddies insisted that it may be important and should be turned in. I went down to the beach where I encountered a naval officer and told of my discovery. He gave me a receipt for the material, and stated that it would be returned to me if it were not important. I have never seen the material since.”

Other soldiers saw or knew of the discovery of Amelia Earhart’s plane, including Earskin J. Nabers, of Baldwyn, Mississippi, a 20-year old private who worked in the secret radio message section of the 8th Marine Regiment’s H&S Communication Platoon. On or about July 6, Nabers received and decoded three messages about the Electra — one announcing its discovery, one stating that the plane would be flown, and the final transmission announcing plans to destroy the plane that night.

Nabers was present when the aluminum plane was torched and burned beyond recognition, as was Sgt. Thomas E. Devine, among others who ignored warnings to stay away from the airfield, which had been declared off-limits. In addition to the many soldiers, Marines and Navy men who saw or knew of the presence and destruction of Amelia Earhart’s Electra on Saipan, three U.S. flag officers later shared their knowledge of the truth with Fred Goerner, acting against policy prohibiting the release of top-secret information, likely in order to encourage the long-suffering Goerner in his quest for the truth.

Three others contacted Devine and corroborated his experience with the Earhart Electra on Saipan: Arthur Nash of Kaneohe, Bay, Oahu, Hawaii, a former captain in the Air Corps who was in a P-47group on Saipan; and former Marines Jerrell H. Chatham, of Avinger, Texas; and Robert L. Sowash, of Manor, Pennsylvania.

In all, 26 Saipan veterans called and wrote to Devine to tell him about their own eyewitness experiences relative to Amelia Earhart and her airplane during the summer of 1944 on Saipan. Their accounts can be found in “Amelia Earhart: The Truth at Last,” and may be the subject of future stories in Marianas Variety.

In late March 1965, a week before Fred Goerner’s meeting with Gen. Wallace M. Greene Jr. at Marine Corps Headquarters in Arlington, Virginia, who reputedly was the officer on Saipan who found the Earhart Electra in a hangar at As Lito Field, former Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz called Goerner in San Francisco. “Now that you’re going to Washington, Fred, I want to tell you Earhart and her navigator did go down in the Marshalls and were picked up by the picked up by the Japanese,” Goerner said Nimitz told him.

Two other U.S. flag officers told Goerner that Amelia Earhart died on Saipan. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, the eighteenth commandant of the Marine Corps, privately admitted the truth to Goerner in a handwritten, August 1971 letter. “General Tommy Watson, who commanded the 2nd Marine Division during the assault on Saipan and stayed on that island after the fall of Okinawa, on one of my seven visits of inspection of his division told me that it had been substantiated that Miss Earhart met her death on Saipan,” the handwritten letter states.

“That is the total knowledge that I have of this incident. In writing to you, I did not realize that you wanted to quote my remarks about Miss Earhart and I would rather that you would not.”

In November 1966, several months after Fred Goerner’s “The Search for Amelia Earhart” was published, retired Gen. Graves B. Erskine, who as a Marine brigadier general was the deputy commander of the V Amphibious Corps during the Saipan invasion, accepted Goerner’s invitation to visit the radio studies of KCBS in San Francisco for an interview. While waiting to go on the air with Goerner, Erskine told Jules Dundes, CBS West Coast vice president, and Dave McElhatton, a KCBS newsman, “It was established that Earhart was on Saipan. You’ll have to dig the rest out for yourselves.”

These fine men had no reason to lie about their knowledge of Earhart on Saipan, and every reason not to say anything at all, yet they risked their reputations, pensions and good standing with the U.S. military establishment by revealing the truth about Earhart to Goerner. The information they shared was still classified top secret, but they wanted to encourage Goerner and let him know that he was on the right track.

Nimitz, Vandegrift and Erskine were all legendary, larger than life figures in the U.S. Pacific war, yet they supported his efforts as much as they could without seriously jeopardizing themselves. They all died of natural causes within a few years of their revelations to Goerner.

As the foregoing witnesses and many others have attested, the presence and death of Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan on Saipan after their July 2, 1937 disappearance is not a legend, rumor or myth. It is a stone, cold fact that the U.S. establishment and its media allies still deny, for very highly political reasons.

Marie S. Castro and the Amelia Earhart Memorial Monument Inc. or AEMMI are still asking for any contributions you can make to the worthy cause of the Amelia Earhart Memorial on Saipan. To contribute, please make your tax-deductible check payable to: Amelia Earhart Memorial Monument, Inc., and send to AEMMI, c/o Marie S. Castro, P.O. Box 500213, Saipan MP 96950. The monument’s success is 100 percent dependent on private donations, and everyone who gives will receive a letter of appreciation from the Earhart Memorial Committee. Thank you.

Thomas E. Devine on Saipan in 1963, two years after his visit to Muriel Earhart Morrissey in July 1961. Devine found the gravesite that he was shown in 1945 by an unidentified Okinawan woman, but didn’t trust Fred Goerner enough to share the discovery with him. Devine never returned to Saipan as he planned to do in 1963, and his decision to keep the gravesite information to himself was one of the worst he ever made.

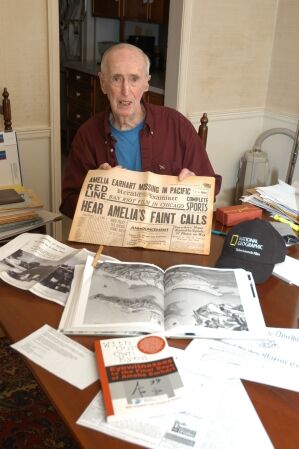

Saipan veteran Robert E. Wallack, whose claim of finding Amelia Earhart’s briefcase in a blown safe on Saipan in July 1944 is among the best-known Earhart-on-Saipan testimonies, pauses in his Woodbridge, Connecticut, home during a November 2006 interview. The media friendly Wallack appeared on several national television specials, including “Unsolved Mysteries” and “Eye to Eye with Connie Chung.”