TWO headlines from the July 12th issue of The Wall Street Journal:

• “China Pays Price for Its One-Child Policy”

• “Earth’s Population Should Peak Before Century”

According to the Journal, the United Nations now “expects China’s population to drop to 639 million by 2100 from 1.4 billion today, a much steeper drop than the 766.7 million it predicted just two years ago.” The Journal says other researchers predict that China will have just 525 million people by the end of the century. The consequence for China is economic decline.

As for the planet’s population, the Journal, citing U.N. estimates, said it is growing more slowly and will peak at a lower level than projected.

The Philippines has long been considered one of the most alarmingly “overpopulated” countries, but in 2022, Sebastian Strangio of The Diplomat reported that the Southeast Asian nation had registered the “sharpest ever” decline in birthrate — the third lowest in the region. In fact, the Philippine fertility rate “has been steadily declining since the 1970s,” but the decline since 2017 is “the sharpest ever recorded.” Why? “As the Philippine economy has grown since the 1960s, birthrates have steadily fallen — a similar pattern to that which has played out in other Southeast Asian nations including Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia.”

And yet as Aidan Grogan of the American Institute for Economic Research has pointed out, “overpopulation concerns are [still] widespread among adults across the planet, with nearly half of sampled Americans believing that the world’s population is too high.”

This “theory of overpopulation, and the collectivist idea that human reproduction must be limited, even by force, is nothing new,” Grogan said. “It first appeared in the ancient Mesopotamian Atrahasis epic [from the 18th century B.C.], where the gods control the human population by infertility, infanticide, and appointing a priest class to limit childbirth.” In ancient Greece, Grogan added, Plato and Aristotle endorsed population control.

However, the “decline of Greek civilization in the second century BC…was not a consequence of an excess number of births, but precisely the opposite. Polybius attributed the downfall of Greece in his time to a decay of population which emptied out the cities and resulted in a failure of productiveness.”

“Two millennia later,” Grogan said, “English economist Thomas Malthus resurrected the old Mesopotamian myth with his 1798 ‘An Essay on the Principle of Population.’ Malthus claimed that population growth increases geometrically while food production increases only arithmetically, which he believed would lead to widespread famine if the rapid propagation of humanity were not obstructed.” To prevent the end of the world — “by any means necessary,” as today’s global saviors would say — he proposed policies to “make the streets narrower, crowd more people into the houses, and court the return of the plague.” He also recommended banning “specific remedies for ravaging diseases.”

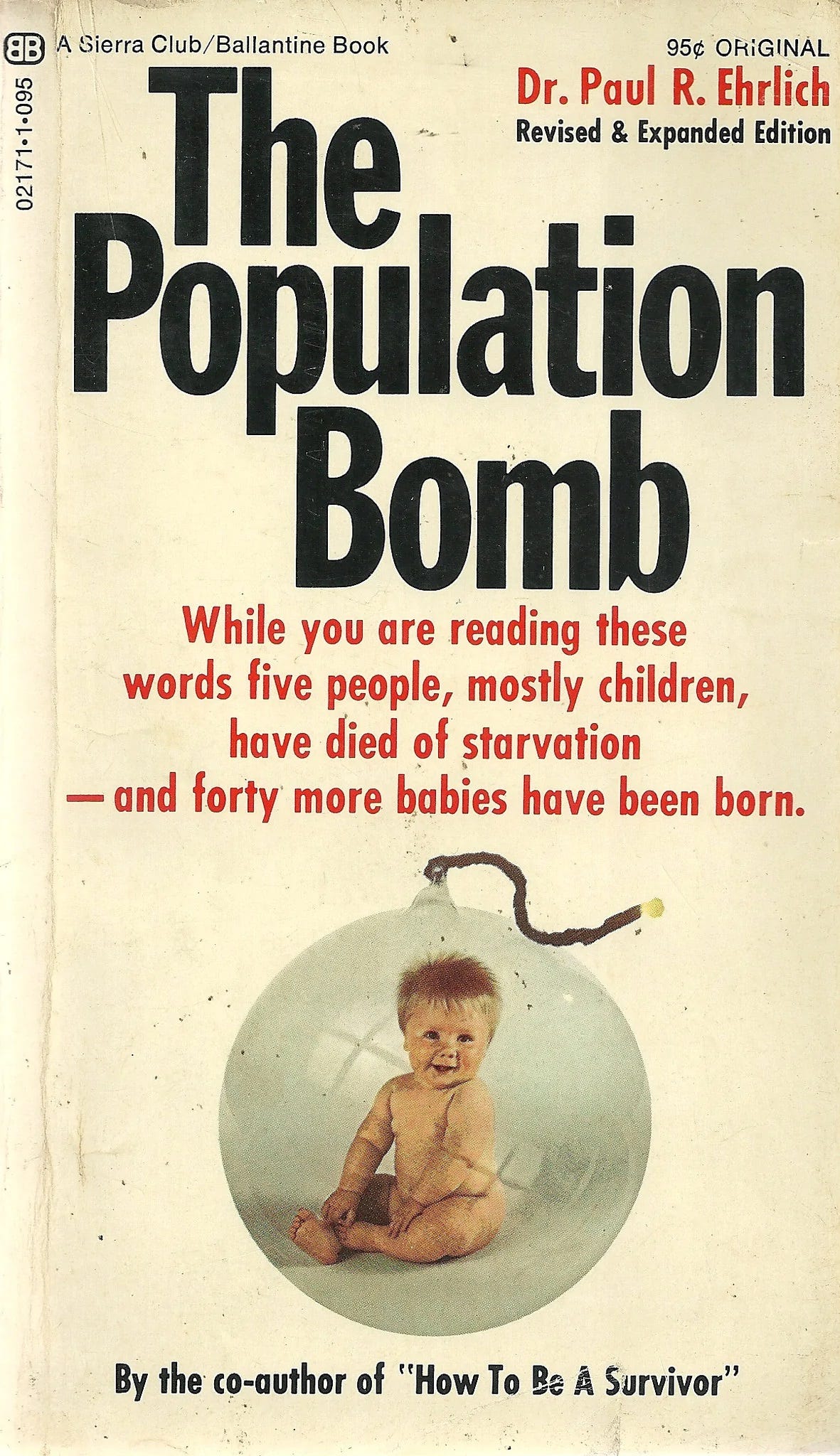

170 years later, another highly intelligent man of science, Stanford biologist Paul R. Ehrlich, published “The Population Bomb,” which predicted imminent worldwide famines and other catastrophes due to overpopulation. “We can no longer afford merely to treat the symptom of the cancer of population growth,” he wrote in 1968; “the cancer itself must be cut out. Population control is the only answer.”

Grogan noted that at “the time of the publication of Ehrlich’s doomsday book…, the world’s population stood at 3.6 billion, and nearly half of people worldwide were living in poverty. Over the next five decades, the global population more than doubled to 7.7 billion, yet fewer than 9 percent of people remain in poverty today, and famines have virtually disappeared.”

Grogan said recent research from Gale L. Pooley and Marian L. Tupy shows that “for every one-percent increase in population, commodity prices tend to fall by around one percent. In the years 1980-2017, the planet’s resources became 380 percent more abundant.”

But many of us still believe that the world will end soon, one way or another.

Says British author Matt Ridley:

“The bookshops are groaning under ziggurats of pessimism. The airwaves are crammed with doom. In my own adult lifetime, I have listened to the implacable predictions of growing poverty, coming famines, expanding deserts, imminent plagues, impending water wars, inevitable oil exhaustion, mineral shortages, falling sperm counts, thinning ozone, acidifying rain, nuclear winters, mad-cow epidemics, Y2K computer bugs, killer bees, sex-change fish, global warming, ocean acidification and even asteroid impacts that would presently bring this happy interlude to a terrible end. I cannot recall a time when one or other of these scares was not solemnly espoused by sober, distinguished and serious elites and hysterically echoed by the media. I cannot recall a time when I was not being urged by somebody that the world could only survive if it abandoned the foolish goal of economic growth. The fashionable reason for pessimism changed, but the pessimism was constant. In the 1960s the population explosion and global famine were top of the charts, in the 1970s the exhaustion of resources, in the 1980s acid rain, in the 1990s pandemics, in the 2000s global warming. One by one these scares came and (all but the last) went.”

Marian L. Tupy says “humanity suffers from a negativity bias, or ‘vigilance for bad things around us.’ Consequently, there is a market for purveyors of bad news, be they doomsayers who claim that overpopulation will cause mass starvation or scaremongers who claim that we are running out of natural resources.”

He adds, “The negativity bias is deeply ingrained in our brains. It cannot be wished away. The best that we can do is to realize that we are suffering from it.”

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com