ON July 31, 1945, the Project Alberta team on Tinian, working with the 509th Composite Group, conducted a complete dress rehearsal of the Little Boy atomic bomb drop. Maj. Charles Sweeney piloted his plane, the Great Artist, and Capt. George Marquardt piloted Necessary Evil, accompanied by Tibbets, who was piloting the yet unnamed Enola Gay. They flew from Tinian to Iwo Jima, where an atomic bomb loading pit had been constructed. If something happened to Enola Gay along the way, they were to land at Iwo, move the bomb from Enola Gay to the standby aircraft, the Big Stink. Tibbets would then fly Big Stink to the target. The test was deemed fully successful.

Gen. Carl Spaatz, now commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific with headquarters on Guam, had arrived on Guam and took command of all B-29 operations (Farrell, Don A., “Seabees and Superforts at War,” p. 429). He allowed General LeMay to continue managing ongoing missions. The 1,000-plane mission on Aug. 1 did not faze the Japanese military leadership. General LeMay received orders that “depending on weather,” the first atomic strike mission would proceed “on or after Aug. 3,” allowing President Truman time to leave Potsdam aboard the ship Augusta. Truman would handle the “fallout” from the first atomic bomb drop aboard ship.

Three “gadgets,” the precisely shaped high-explosive charges for plutonium-based, implosion-type bombs, arrived on Tinian. Of the three, Capt. Deak Parsons, USN, chose F-31 for the Fat Man mission. If the Japanese did not surrender after the Little Boy drop (containing 141 pounds of Uranium), F-31 would be armed and made ready for use. Aug. 10 was chosen for the Fat Man drop (Farrell, Don A. “Tinian and The Bomb,” p. 246). The original plan, suggested by Rear Adm. William Purnell, Navy representative to the Manhattan Project, was a one-two punch, followed by a threat of a third bomb.

Early on the morning of Aug. 4, LeMay’s weathermen predicted clear skies over Honshu on Aug. 5. Little Boy was moved from Assembly Building #1 to the atomic bomb pit. Enola Gay was backed over the pit, and the bomb was loaded into the plane.

At about 2:45 a.m. Monday morning, Aug. 6, 1945, Col. Paul Tibbets pushed Enola Gay to 155 mph and lifted off from Runway Able. He had perfect weather, with the perfect crew and the perfect B-29 (Farrell, “Tinian and The Bomb,” p. 264-5). Maj. Charles Sweeney, in command of The Great Artist, his regular plane and with his regular crew, took off with scientific equipment aboard. The Necessary Evil took off with the photographic equipment. After the three Silverplates were airborne, Tibbets told the crews that the bomb they were carrying was an atomic bomb.

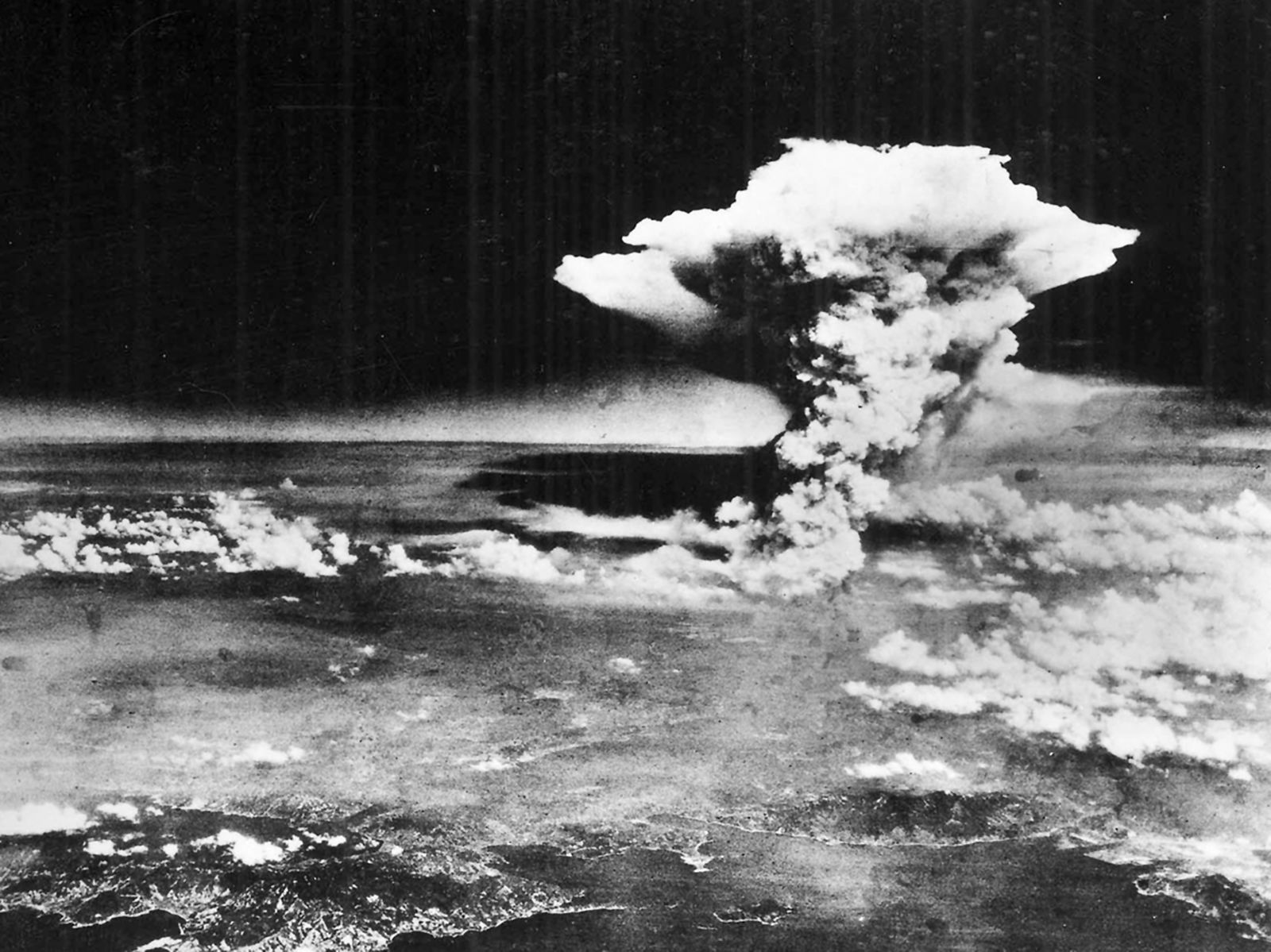

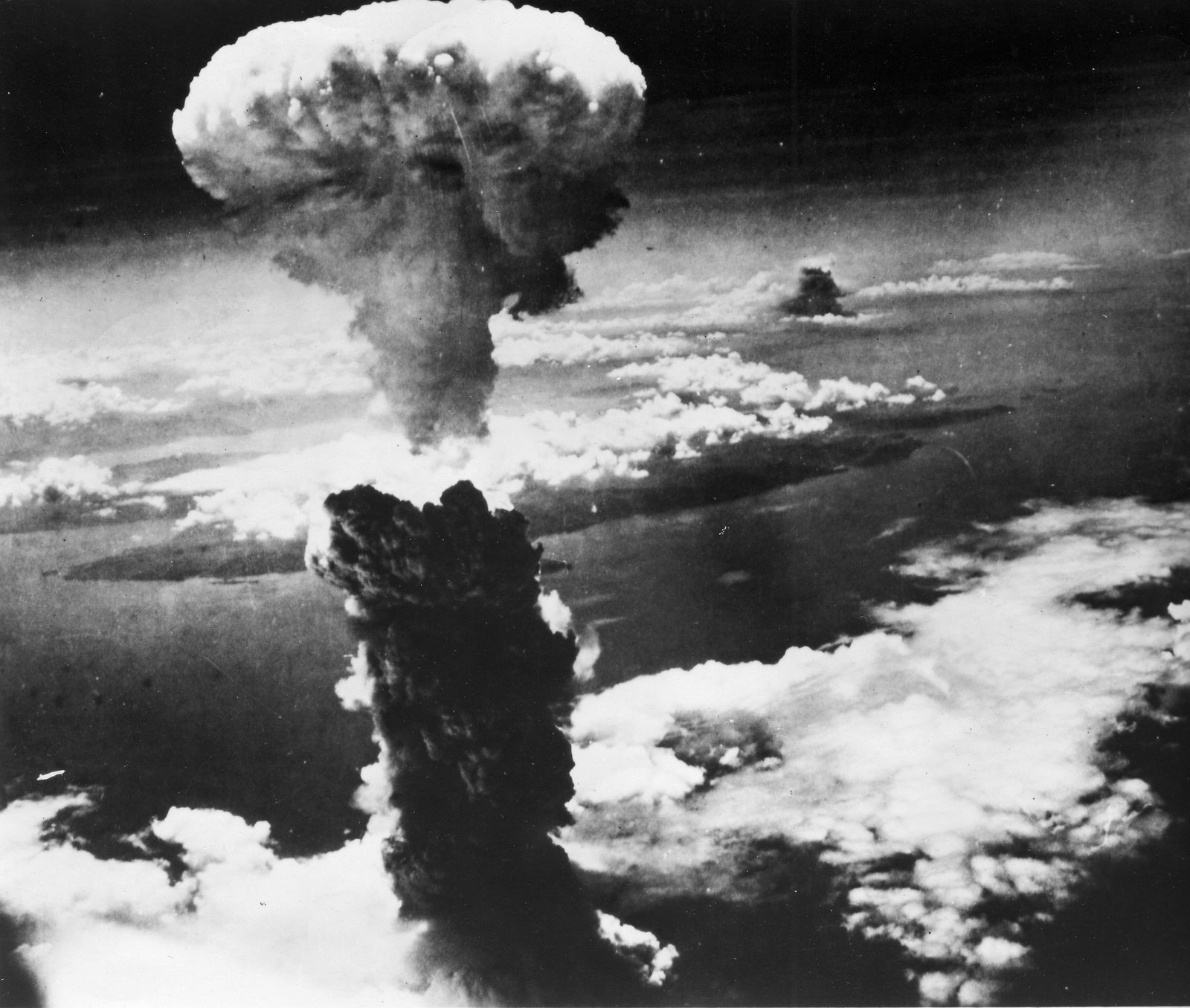

They rendezvoused at Iwo Jima, the Silverplate Big Stink awaited, ready to complete the mission, if necessary. Enola Gay had run smoothly, so they did not stop. (Imagine how the media would have handled the story of the dropping of the first atomic bomb by a B-29 named Big Stink!). With a report that the weather was clear over Hiroshima, Tibbets flew directly to the target. At 09:14:17, the bombardier spotted the pre-designated target through his bomb sight and dropped the bomb. Forty-three seconds later, it exploded, obliterating the entire city. Tibbets and his team had flown a perfect mission, a milk run to Hiroshima. Bob Caron, the tail gunner in Enola Gay, took the now-famous photo of the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima.

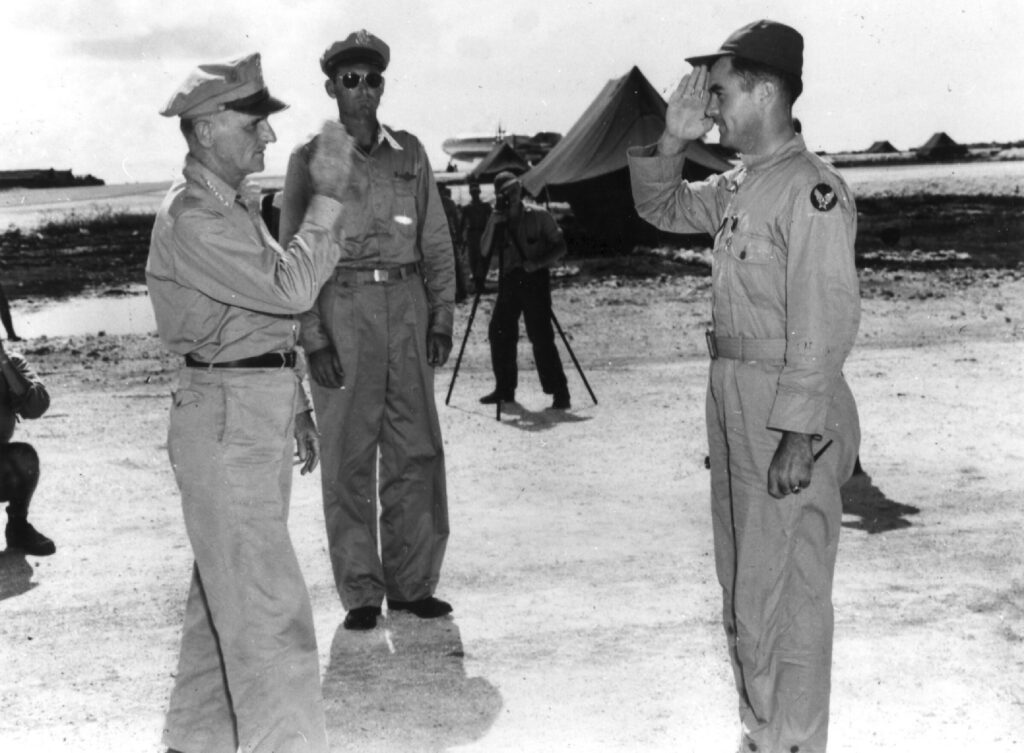

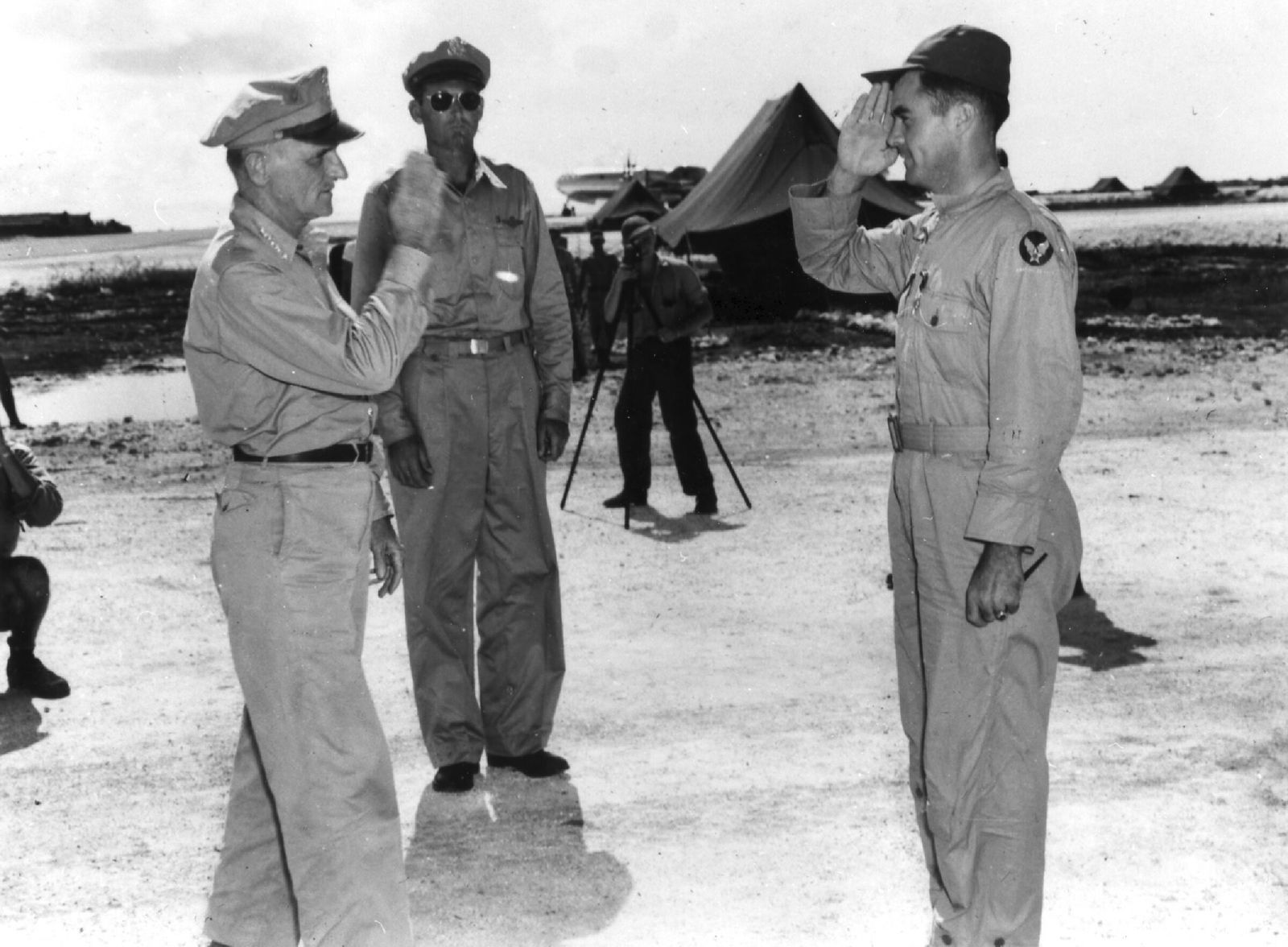

The Enola Gay touched down on Tinian at 2:58 p.m. Tibbets was met at plane-side by General Spaatz, who pinned the Distinguished Service Medal on his chest. President Truman, aboard the Augusta, ordered the prearranged announcement released to the media. Overnight, Tibbets became the most famous man in the world.

Once again, President Truman requested that the Japanese surrender. If not, “they may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth (“Tinian and The Bomb,” p. 290-1).”

Then things began to go bad. At a meeting on Guam the next morning, Aug. 7. LeMay announced that the weather was turning bad over Japan. They would have to either move the drop from Aug. 11 up to Aug. 9 or wait a week or so for the weather to clear. Tibbets expressed regret that the schedule could not be advanced by two days. The group decided on Aug. 9th as the drop date. Dr. Norman Ramsey, second in command to Oppenheimer, agreed to complete Fat Man in Assembly Building #3, but would only give it an 80% chance of detonation. Not all the new parts that had arrived at Tinian had been field tested.

In a separate meeting afterwards, Tibbets told General LeMay that he would not fly the Fat Man mission. He was giving command to his friend, Maj. Charles Sweeney, the squadron commander. When LeMay asked him why, Tibbets responded: “I’m getting enough publicity. The other guys have worked long and hard and can do the job as well as I can.” One must wonder if Dr. Ramsey’s advice, which gave the Fat Man bomb only an 80% probability of exploding, played a role in his decision not to fly the mission.

Although many Japanese leaders were now prepared to accept the Potsdam Declaration, calling for the unconditional surrender of all Japanese military forces, the military clique decided against it. Emperor Hirohito remained silent.

Meanwhile, Russia decided to join the war. At 4:30 p.m. on August 7, Stalin signed the order for Marshall A. M. Vasilevsky, Commander-in-Chief of Soviet Forces in the Far East, to begin the Manchurian operation at midnight on Aug. 8th (6 p.m. Moscow time).

With no surrender offer from Japan, Gen. Nathan Twining, the new Commander-in-Chief of the 20th Air Force, handed the order for the second atomic bomb strike to General Spaatz, to pass on to General LeMay, to pass on to Colonel Tibbets. The mission would follow the same route to Iwo Jima, but the final rendezvous was identified as the small island of Yakushima, which they had never visited.

On the afternoon of the 8th, Fat Man was loaded into the Silverplate B-29 Bockscar, instead of his usual crew in his usual plane, The Great Artist, which still had all the instruments on board from the Little Boy drop and the Fat Man test drop that day.

Aug. 9, 1945, the day that Japan’s future course was charted, “Special Mission #16 was launched. It would not be flown by the “perfect crew, in the perfect plane, with perfect weather. Instead, they would use a less-than-perfect plane, with a less experienced crew, and the weather was turning bad.

At 0348 a.m., after discovering a malfunctioning fuel pump system, Seeney decided to fly anyway. Bockscar lifted off from Runway Able. Then, The Great Artist, the instrument plane, took off from Baker, and V-90, the observation plane, from Runway Charlie.

As Bockscar neared Yakushima, he climbed to bombing altitude and began circling, waiting for the other two planes to make the rendezvous. Fred Bock, usually piloting his plane, Bockscar, arrived five minutes later in The Great Artist with the instrument packages. Hopkins in V-90 was a no-show. After wasting 45 minutes of fuel at high altitude waiting for V-90, Sweeney turned towards Kokura, the primary target, without V-90.

Kokura was masked by cloud cover. After using more precious fuel in an attempt to find a hole in the clouds, and with very low fuel remaining, Sweeney turned Bockscar toward Nagasaki. Finding it also cloud-covered, Sweeney asked Commander Dick Ashworth, the bomb commander, if they could do a radar run. Ashworth, a naval academy graduate, said no. It was against the rules. Things became tense on board Bockscar. They no longer had the fuel to land at Iwo Jima. The only option was to land at Okinawa, which had only been developed for B-24s.

Ashworth finally approved the radar run. But at 12:02 p.m., Tinian time, as they passed over Nagasaki, veteran bombardier Kermit Beahan spied the target through a hole in the clouds. “I’ve got it, Bombs away. I mean bomb away.” It was his 27th birthday present to Japan.

When Fat Man reached 1,650 feet, it exploded. Ironically, it missed the aiming point in the center of town, but hit the Mitsubishi Iron and Steel Works, the same factory that had manufactured the torpedoes used at Pearl Harbor. Because it was on the outskirts of town, it killed far fewer people.

After a harrowing landing at Yontan Airfield, Okinawa, with two engines running out of fuel, they refueled and took off for Tinian. Following a 19-hour flight, they landed at Tinian at 11:06 p.m. There were no Klieg lights on the field and no cameras rolling. The unofficial briefing took place in the Officers’ Club.

At midnight, Emperor Hirohito took matters into his own hands and told the military clique that he had decided to accept the Potsdam Declaration. At 6:45 a.m., August 10, Tokyo Time, the Japanese government transmitted its initial offer to accept the Potsdam terms to the Swiss and Swedish embassies. At about 8:30 a.m., a radio operator on Tinian heard the surrender announcement and, with or without permission, broadcast it live to all units on Tinian.

Aug. 10 was declared a holiday, and an islandwide beer bust broke out.

Despite the malfunctioning B-29, the lack of rendezvous at Yakushima, the cloud cover over both the primary and secondary targets, and the harrowing landing at Yontan, Okinawa, Sweeney had accomplished his primary task, dropping the second bomb by visual sighting. Knocking out the factory that had manufactured the Pearl Harbor torpedoes was just icing on the cake.

Over 200,000 Japanese lives had been lost in the two atomic bombings. However, the invasion of Japan scheduled for November 1 had been prevented, saving millions of lives.

Still, some Japanese military officers were planning a military coup. If the Japanese reneged on the surrender deal, Oppenheimer predicted that the next plutonium sphere would be ready for shipment to Tinian by Aug. 13th.

Col. Paul Tibbets, right, salutes Gen. Carl Spaatz.

A mushroom cloud billows into the sky about one hour after an atomic bomb was detonated above Hiroshima, Japan.

Major Sweeney’s crew returns.

Nagasaki

Party time