“This program was implemented in 1985. This will be the first year we cannot provide this help.”

<p style=”text-align: right;”><strong>—Lauri Ogumoro, Karidat Executive Director</strong>

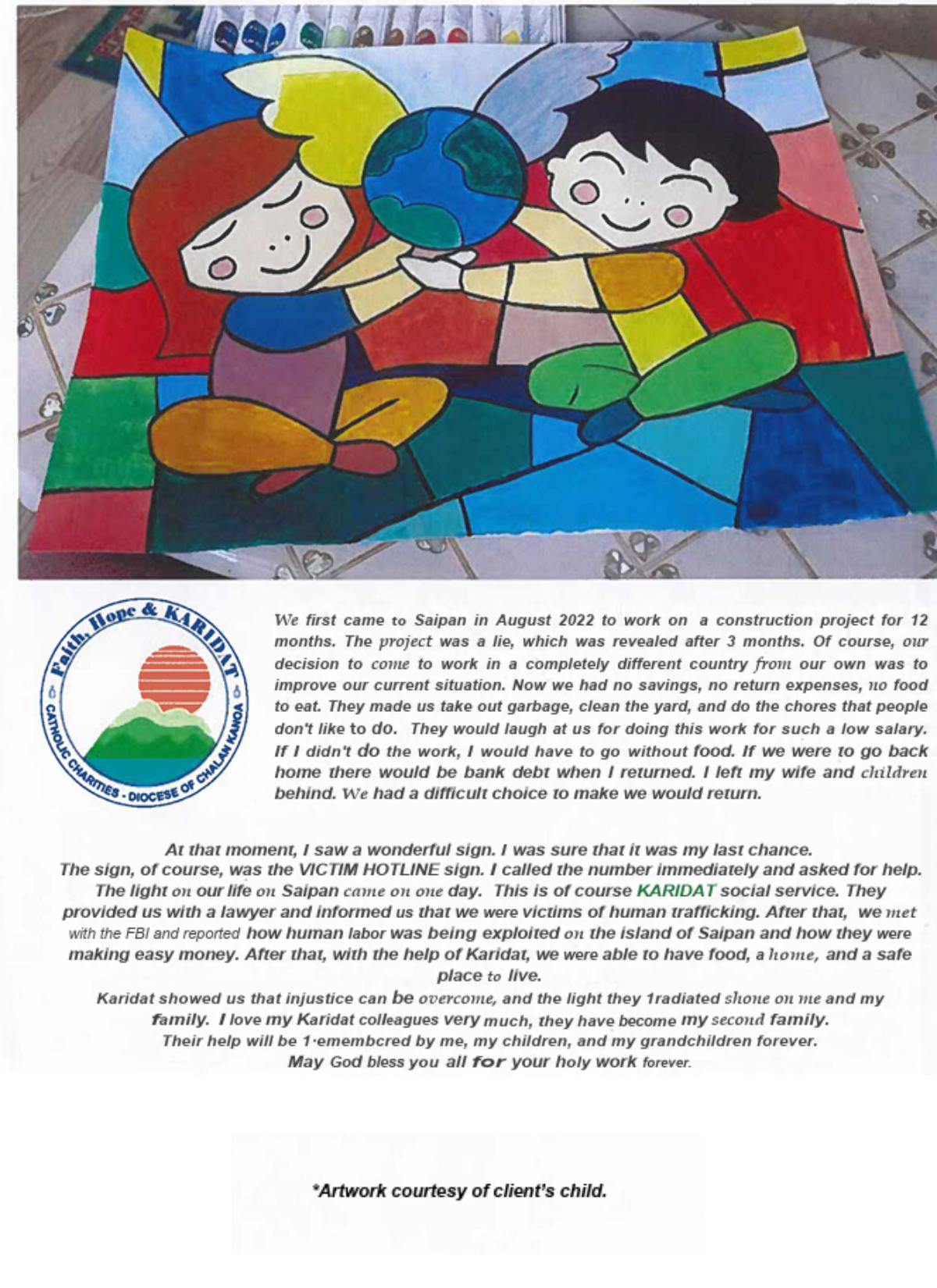

KARIDAT has been CNMI’s quiet guardian—feeding the hungry, sheltering the displaced, and stitching hope into the fabric of a community that often has nowhere else to turn. But now, that safety net is unraveling. For the first time since 1985, its Emergency Food and Shelter Program sits empty, leaving 91 families on a waiting list with no relief in sight.

“Due to a hold on the Emergency Food and Shelter Program, Karidat no longer has funds to provide food and rental assistance to our needy community members,” says Executive Director Lauri Ogumoro. “This program was implemented in 1985. This will be the first year we cannot provide this help.”

The loss is not just bureaucratic; it’s measured in empty pantries and precarious roofs.

The human cost of cuts

The Emergency Food and Shelter Program was never just a line item. It kept families from sleeping in cars and put meals on tables when jobs vanished or typhoons struck. Now, Karidat’s pantry survives on patchwork support: “The parishes in the Diocese of Chalan Kanoa and a grant from the Church of Latter-Day Saints have been helping our food pantry in the meantime.”

But Ogumoro’s warning is stark: “When our existing funding runs out, we will no longer be able to assist.”

Remarkably, other programs still operate—for now.

“So far—knock on wood—just the Emergency Food and Shelter program is impacted,” she notes.

Staff remain, but the scaled-back services reveal a grim truth: federal cuts strike where they hurt most.

Searching for solutions in a broken system

Karidat’s scramble for alternatives mirrors a broader crisis. “We are exploring other grants that may be available to assist with our specific needs,” Ogumoro says. But grants are a slow salve for a bleeding wound. “There may be alternative revenue streams and partnerships, but we have to explore them, which means writing the grants, and being on the right timeline with the grantor cycle.”

Through it all, the nonprofit’s compass remains fixed: “Karidat always prioritizes client services first as they are the reason we remain open.” Yet resolve can’t conjure funds from thin air.

An uncertain future, a call to action

The path forward is uncharted. “Times are very economically difficult for donors in the CNMI right now, so we are looking into foundation grants,” Ogumoro admits.

Even collaboration has limits: “Karidat has a strong history of working with other nonprofits, and the local government has helped when needed—but we have not relied on them, preferring to utilize federal funds. Unfortunately, times are quite different now.”

When pressed about sustainability, her answer is hauntingly simple: “Karidat programs rely on federal programs. We will have to see how things go.”

The community’s role has never been more critical. “Donations of food and clothing are always welcome—especially canned food to help us fill our pantry,” she urges. But the unspoken question lingers: Can Saipan rally to replace what Washington has withdrawn?

As Karidat marks 45 years of service, its legacy is clear—but its future hinges on a choice. Will the systems built to protect the vulnerable adapt, or will they let the net collapse? The answer will define not just Karidat’s next chapter, but the soul of the community it serves.