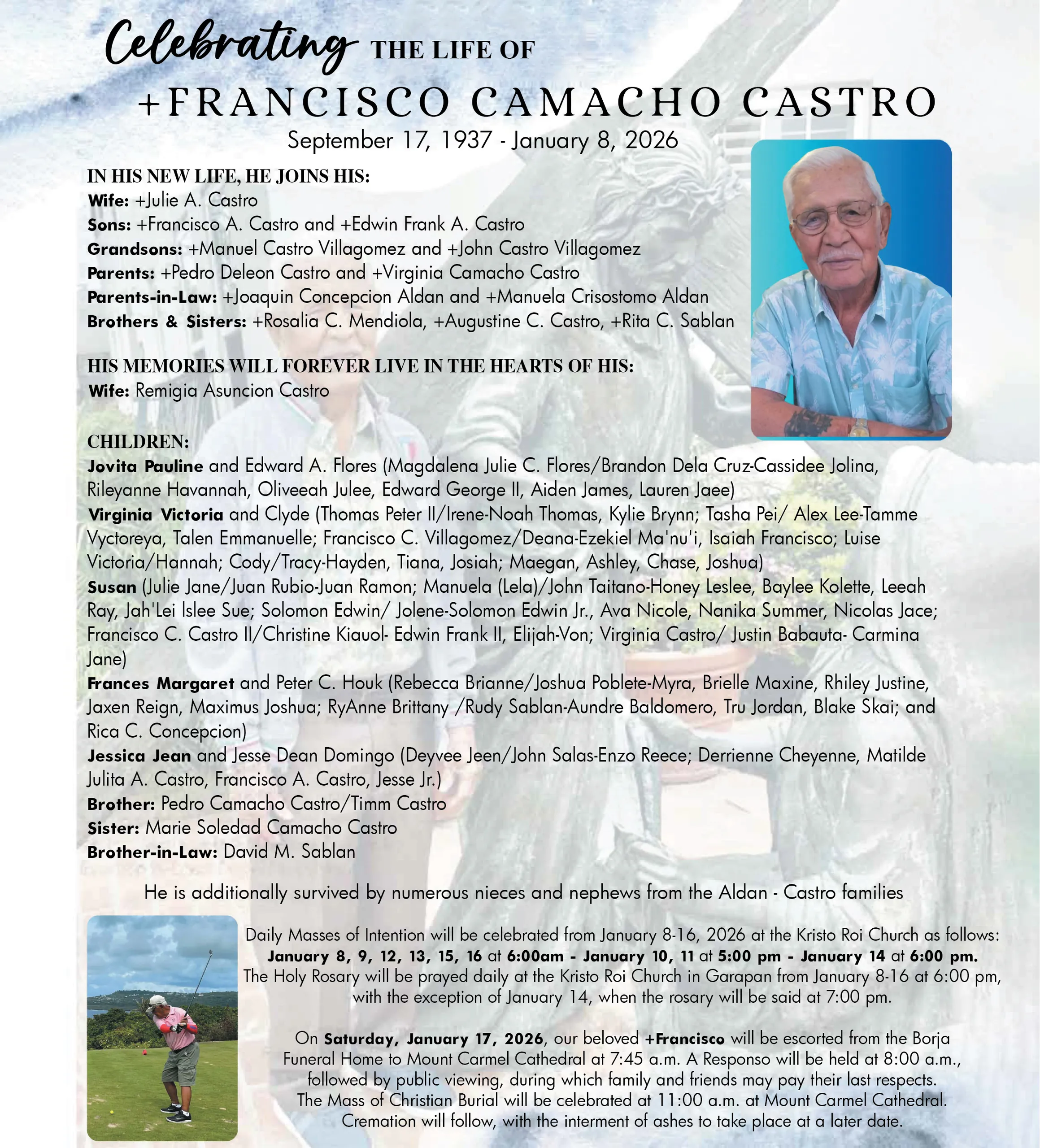

CNMI Mental Health Court Judge Lillian A. Tenorio, right, with Court Docket Manager Victoria Matsunaga during the 2025 Treatment Court Summit at Crowne Plaza Saipan on Thursday.

Photo by Bryan Manabat

THE Mental Health Court under the CNMI Superior Court has been transforming how the justice system handles individuals with serious mental illnesses, Court Docket Manager Victoria Matsunaga said.

Established in 2021, the court was developed in response to growing mental health concerns in the community.

“The court provides treatment-focused alternatives to incarceration for eligible participants,” Matsunaga said.

The Mental Health Court operates alongside the Drug Court, but with a distinct focus.

Participants in Drug Court are treated for substance use disorders, while those in the Mental Health Court docket receive care for serious mental illnesses, Matsunaga said.

They’re both treatment courts, but they treat participants in different ways, she added.

“The court uses a whole person approach, evaluating each individual’s mental health, substance use, and social support systems,” Matsunaga said.

“We look at the person and say, ‘Okay, this is their mental illness. How can we treat that first?’ Then we can look at the rest — do they have a substance use disorder? Do they need family or social support?”

Since its launch, the Mental Health Court has handled seven cases. Referrals come from the Office of the Attorney General and the Public Defender’s Office.

“There’s an eligibility process that starts with legal eligibility. If they qualify, we then assess clinical eligibility,” Matsunaga said.

Participants are often already incarcerated when referred, she added.

“They could be incarcerated, and then we take them under our court,” she said. “It’s more focused on medication management and…treatment.”

Matsunaga said the Mental Health Court’s goal “is not only to reduce recidivism but also to address the root causes of criminal behavior linked to mental illness.”

“Treatment courts work. They save lives. They save money. They save time,” Matsunaga added.

She said national data “shows treatment courts can save up to $6,000 per individual compared to traditional incarceration.”

Plans are underway to expand the treatment court model to other populations, including veterans.

“Veterans are their own specific group of people. That’s not to say a person suffering from a mental illness doesn’t also have a substance use disorder — it’s just about which one is more prominent,” Matsunaga said.

She said there’s also a broader issue: the lack of comprehensive mental health data in the CNMI.

“We don’t have a specific number or dataset that tells us how many people suffer from mental illness,” Matsunaga said. “But national surveys show higher rates of anxiety and depression among Pacific Islanders.”

With the CNMI’s population being predominantly Asian Pacific Islander, the need for culturally informed mental health services is critical, she said.

“The leading cause of death for [Asian Pacific Islander] adolescents is suicide. That tells me there’s an issue we’re not addressing,” Matsunaga said.

As the Mental Health Court continues to grow, she hopes it will serve as a model for broader mental health reform.

“We’re just dealing with justice-involved individuals, but it’s a step. Every step counts, no matter how big or small — as long as we’re moving forward together,” Matsunaga said.

Judge Lillian A. Tenorio presides over the Mental Health Court.