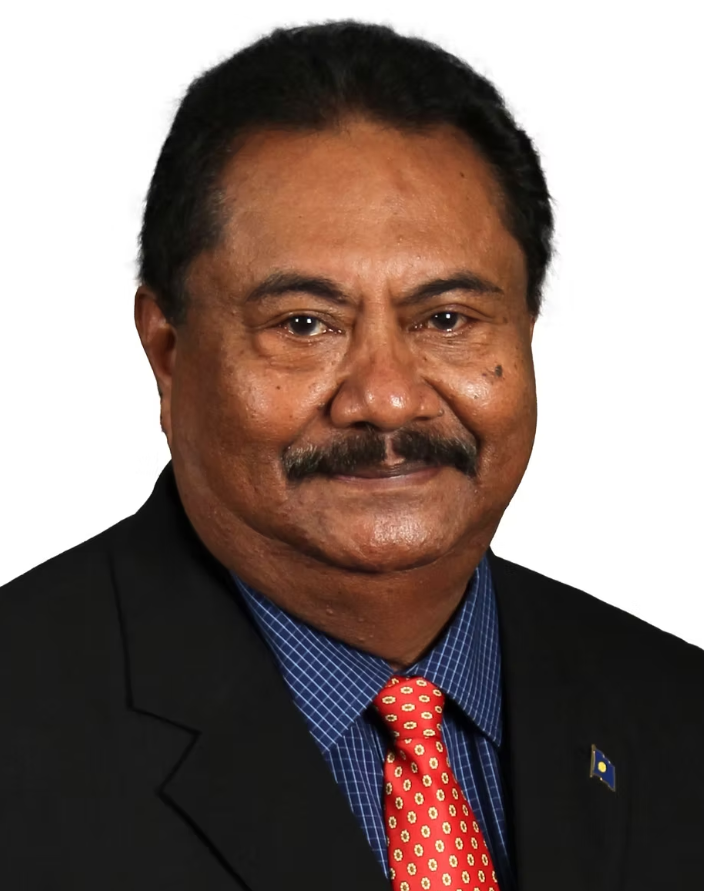

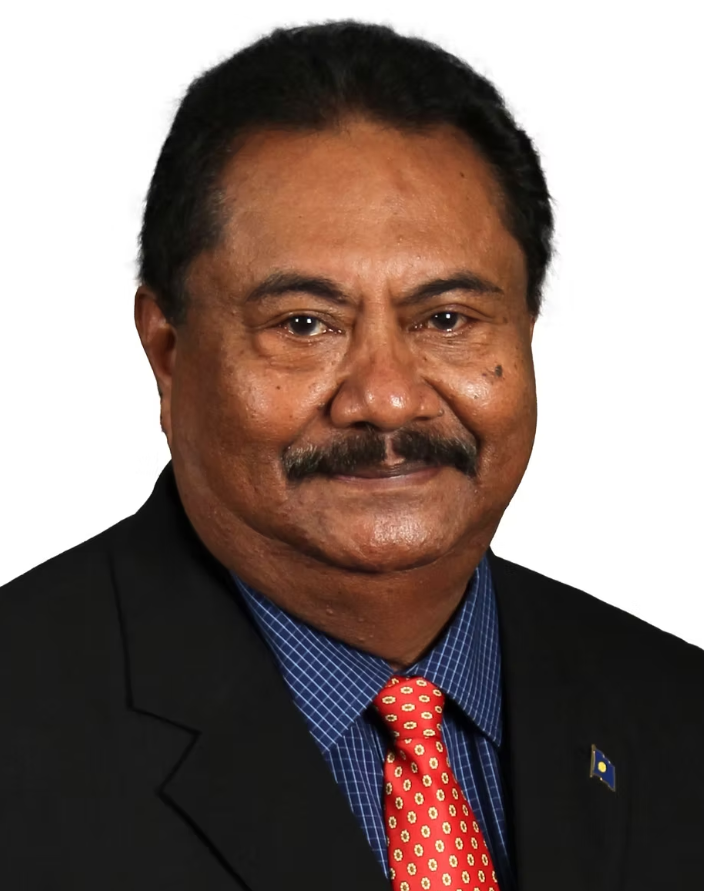

Hokkons Baules

KOROR (Island Times/Pacnews) — A proposal from the United States to relocate asylum seekers to Palau has been firmly rejected by the OEK, Palau’s National Congress, and the Council of Chiefs, with leaders calling it “dead on arrival.”

The proposal, presented to Palauan leadership on July 18 by President Surangel Whipps Jr. and U.S Ambassador Joel Ehrendreich, sought Palau’s agreement to temporarily host so-called “third-country nationals” — individuals who are seeking asylum in the United States but cannot be returned to their country of origin.

However, the plan met swift opposition. On July 19, the leaders of both houses of the Olbiil Era Kelulau, Senate President Hokkons Baules and House Speaker Gibson Kanai, sent a joint letter to President Whipps advising him not to proceed.

“We strongly advise against proceeding further on this matter,” the letter stated, adding that while Palau is a strong U.S ally, “we cannot afford to overpromise or commit to something we cannot fulfill.”

The Council of Chiefs, which advises the president and includes traditional leaders from Palau’s 16 states, echoed the congressional stance.

In their formal response, the chiefs urged President Whipps not to sign the agreement, emphasizing the weight of such a decision on a small island nation.

“Our position has not been an easy one to reach because the request comes to us from our number one ally, the U.S,” the council wrote.

“We are certain, however, that our best friend understands our precarious and fragile situation as a tiny island nation seeking to exist in this complex world.”

Palau currently lacks a legal framework to accommodate asylum seekers or refugees, and any agreement could require approval from two-thirds of both houses of the OEK.

The country is also not a signatory to the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, further complicating any attempt to take on such a role.

Given the strong and immediate opposition from both the legislature and the Council of Chiefs, the likelihood of the U.S proposal advancing appears slim. As one lawmaker described it, the plan is effectively “DOA” — dead on arrival.

Meanwhile, U.S Ambassador to Palau Joel Ehrendreich told Palauan leaders that individuals likely to be sent to Palau under a proposed asylum agreement are those whose claims have been deemed inadmissible or abandoned in the United States, raising concerns over the legal, logistical, and ethical implications of the arrangement.

During a July 18 meeting with Palau’s Council of Chiefs, members of the OEK, and President Surangel Whipps Jr, Ehrendreich outlined the proposed cooperation agreement, emphasizing that Palau is not obligated to accept any individuals at this stage.

“This first agreement is just a framework — that yes, we are willing to have a discussion later on about specific individuals,” Ehrendreich said. “This agreement does not obligate Palau to accept any individuals at this time or require it to agree in the future.”

He added that the United States is in dialogue with several nations, including Palau, as it seeks third-party countries willing to accept individuals whose asylum claims in the U.S have been dismissed or abandoned.

According to Ehrendreich, the people potentially relocated to Palau are not those fleeing active persecution but individuals whose asylum applications in the U.S were considered invalid or who voluntarily chose not to return to their home countries.

“The administration feels that a number of those people are abusing our immigration system,” he said. “They come to the United States not because they fear persecution for race or political affiliation, but because they are trying to game the U.S system.”

He explained that more than one million asylum claims are currently pending in the United States, with hearings backlogged for over five years. During this period, asylum applicants can live and work legally and may even start families, whose children could be granted U.S citizenship.

“This creates a situation that this administration wants to prevent by encouraging people to apply from outside and reducing incentives to make false claims,” he said.

The Asylum Support Agreement would give Palau the right to accept or decline each individual referred by the U.S., explicitly excluding unaccompanied minors and allowing either party to terminate the agreement at any time. While not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention, Palau would be expected to care for individuals while their protection claims are processed and would be prohibited from sending them back to their countries of origin during that time.

Ehrendreich noted that potential financial support would be discussed during a second phase of negotiations, only after Palau agrees to the initial framework.

Ehrendreich emphasized that Palau would not serve as a processing center like Nauru or Papua New Guinea under Australia’s offshore asylum policy. Instead, Palau would be considered a “safe third country” for those seeking protection — a term often used in U.S. agreements with countries such as Guatemala and Honduras.