THE “authoritarian temptation” is a penchant largely found among intellectuals and those who consider themselves intelligent. They believe that democracy is too messy, too chaotic to accomplish what must done to save the “demos” — Greek for “the people — from themselves. Most people are, alas, burdened by ingrained biases to discern right from wrong — as defined by their intellectual betters. In elections, not surprisingly, the people usually tend to vote for the “wrong” candidates.

What we need is a “meritocracy” — governance by those deemed most capable due to their intellect, education, or expertise. Who choses them? Well, they themselves. After all, most voters are “too dense” to know a great leader if they see one. That’s why, more often than not, they vote for politicians whom they will eventually denounce.

Now imagine if our leaders are intellectuals and experts. They will be “above politics.” They will be incorruptible. They will craft wise policies, and actually implement them.

This is not a hypothetical scenario. In the 20th century, in many countries all over the world, several idealistic leaders took over the reins of government, but the results were mostly disastrous. Acquiring power, it seems, does not necessarily improve human nature. Leaders, however pure-hearted, remain human and are still susceptible to the follies that afflict us lesser mortals — with the crucial difference that leaders, unlike us, wield power over others.

Lifelong students of history, the framers of the American Constitution were keenly aware of this truism. (See “The Federalist Papers.”) It is also the key lesson of public choice theory, which applies the ideas of economics to politics. Voters, politicians, and government officials make decisions, not as perfect problem-solvers, but as individuals with their own self-interests.

Every time we forget this time-tested concept we end up enamored with the latest political savior who promises to, once and for all, solve society’s problems.

Prior to World War II, intellectuals were impressed with the “achievements” of Mussolini, Hitler and Stalin. (“I have seen the future, and it works!” said an American investigative journalist after visiting the USSR.) In the post-WWII era, the idol of choice for many activists was Mao Zedong. China’s Great Helmsman was a poet, writer, philosopher, military leader and voracious book reader. He wanted to build a just, equitable and prosperous China. He wore old pants that had their backside patched up. He disliked new shoes. He lived simply, frugally, or so we were told.

Mao and his Communist Party had absolute power to re-make China. And re-make China they did through large-scale visionary policies…that pushed their country to the brink. Through his “Great Leap Forward” campaign, Mao wanted China to be industrialized and achieve economic progress as quickly as possible. Result? Economic and agricultural collapse, and tens of millions of people dying of starvation. During that period of time, Mao also declared total war against sparrows, which he said were bad for agriculture. He wanted sparrows exterminated, so they were all killed. Result? Without sparrows, which ate a large number of insects, including locusts, these pests proceeded to destroy crops. China’s rice yields, which were supposed to increase, decreased. China had to import sparrows from the USSR.

Mao never blamed his policies for the catastrophes they unleashed. Instead, like most “enlightened” leaders, he blamed the people for not being enlightened enough. At the age of 72, he launched his most ambitious campaign yet, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Its aim was to change, once and for all, the reactionary, if not selfish, mindset of the people. Result? Social and cultural devastation, economic stagnation, collapse of education, widespread chaos and suffering.

Because of his toxic policies, which aimed to preserve his legacy, Mao unwittingly initiated the process of curing China of the social and economic excesses of Maoism. Post-Mao, China switched to state-led capitalism and achieved tremendous economic growth.

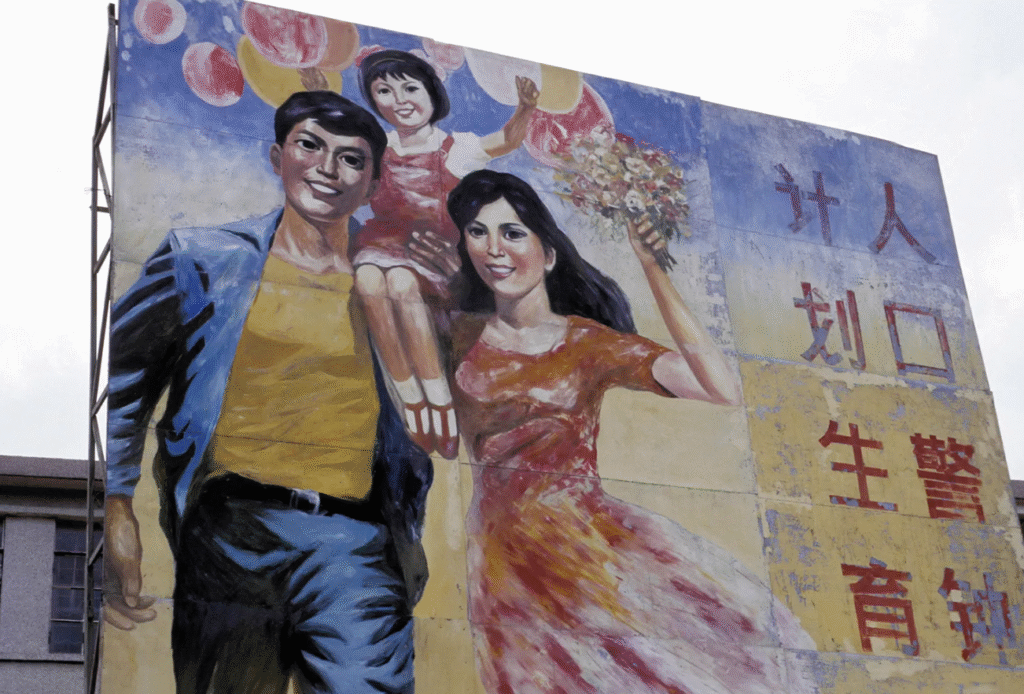

China, however, remained under an authoritarian state. Despite virtually abandoning its ideological underpinnings, the Chinese Communist Party still considered itself the sole arbiter of truth and the stern father of the people. It continued to come up with other “intelligent” policies to, once and for all, “solve” what many intellectuals believed were problems, including “overpopulation.” Hence, the one-child policy that was devised by an actual rocket scientist.

Result? Sex-selective abortions. Female infanticide. Reduced birth rates. Labor shortages. Reduced consumer base. A growing elderly population that has placed pressure on social services, pensions and healthcare systems. Economic slowdown.

In a functioning democracy that adheres to the rule of law, many leaders will continue to overpromise and make mistakes, but they are subject to checks and balances, and regular elections. They cannot implement “once and for all” solutions unless backed by an overwhelming majority of voters, which is hard to secure. And any major policy, moreover, can always be changed, watered down or even discarded after the next election.

I’ve noticed, in any case, that many well-meaning folks who admire the Chinese government’s “political will” to implement “good policies” (especially regarding climate change) are also reluctant to move to China.

Freedom and democracy don’t “solve” everything — they’re not meant to, but they also won’t lead to the deaths of tens of millions of people in the name of a better tomorrow…that never arrives.

“A better tomorrow,” incidentally, is one of the most telling catchphrases used by those likely to succumb to the authoritarian temptation.

Authoritarianism presupposes that everything has been settled already. It doesn’t tolerate arguments. Democracy is an endless argument.

To be sure, many of us will continue to admire the decisiveness of “strong” leaders who are guided solely by what is “good and true.”

But there’s the rub: Not everyone agrees on what exactly is “good and true.”

Democracy is like a doctor whose patients are hypochondriacs. Dr. Democracy offers mostly “tentative” solutions, subject to the voters’ desires, which the doctor knows will inevitably change sooner or later. In contrast, Dr. Authoritarianism is the one who declares that the operation was a success, but the patient died.

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com