IN “Factfulness,” a book published four years ago, Swedish physician and academic Hans Rosling said the top global risk that concerned him the most was a global pandemic. This was two years before the Covid-19 outbreak. It was also Rosling who pointed out that what we know about the world is most likely outdated already.

Many of us, for example, are convinced that the English scholar Thomas Malthus was right, even if we don’t know who he was. In 1798, he wrote that population growth would eventually outstrip our ability to produce food and other resources to keep us alive. In 1968, Stanford University Professor Paul R. Ehrlich updated the Malthusian doomsday scenario in his widely popular book, “The Population Bomb”:

“The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate….”

From the May 22, 2021 issue of the New York Times:

“All over the world, countries are confronting population stagnation and a fertility bust, a dizzying reversal unmatched in recorded history that will make first-birthday parties a rarer sight than funerals, and empty homes a common eyesore.

“Maternity wards are already shutting down in Italy. Ghost cities are appearing in northeastern China. Universities in South Korea can’t find enough students, and in Germany, hundreds of thousands of properties have been razed, with the land turned into parks.

“Like an avalanche, the demographic forces — pushing toward more deaths than births — seem to be expanding and accelerating. Though some countries continue to see their populations grow, especially in Africa, fertility rates are falling nearly everywhere else. Demographers now predict that by the latter half of the century or possibly earlier, the global population will enter a sustained decline for the first time.”

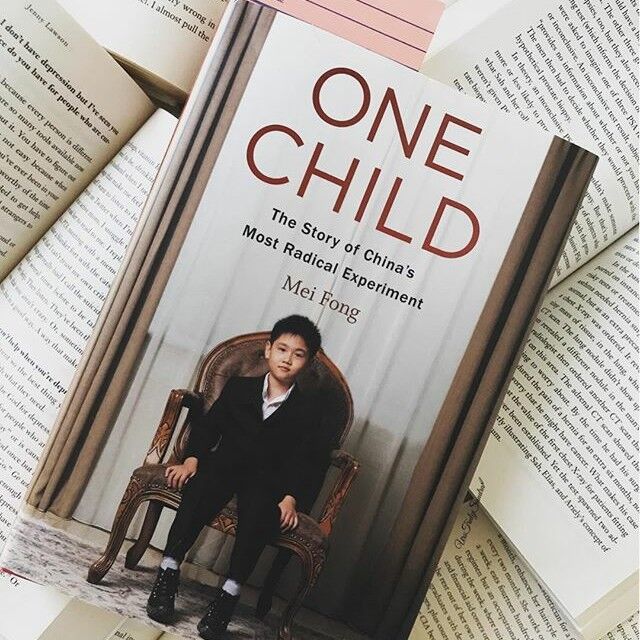

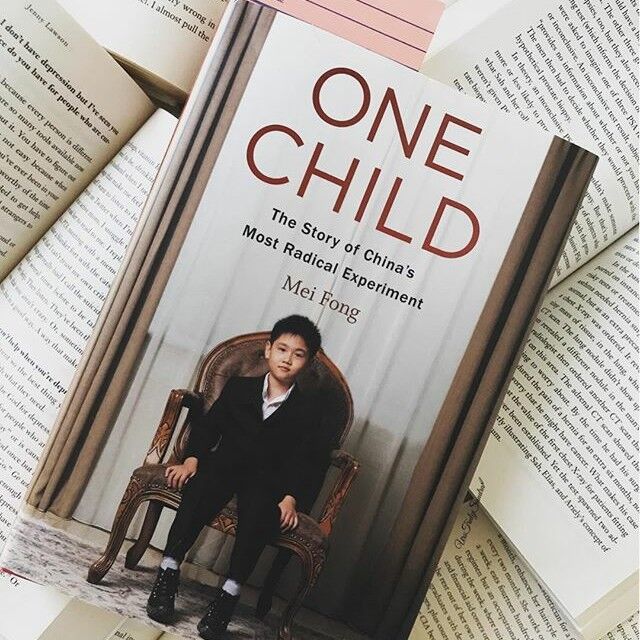

In 2016, Mei Fong’s book on China’s one-child policy was published. She’s a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, and I’ve read her book six years ago, but I’m only writing about it now because discussing election-year politics is more depressing.

In any case, the Malthusian-Ehrlichean inspired one-child policy has been disastrous for China. When it was first implemented in 1980, it was touted as a “solution” based on “science.” Fong noted that it was a team of rocket scientists who played a major role in the one-child policy rollout.

“Looking back,” Fong wrote, “it seems amazing how confident China’s rocketmen were in their projections of population growth, refusing to factor in how human behavior or technology might change their projections. They appeared utterly sure of the correctness of their solution.”

Sounds familiar?

According to Fong, “The excesses of the one-child policy, such as forced sterilizations and abortions, would eventually meet with global opprobrium. Balanced against this, however, is the world’s grudging admiration for China’s soaring economic growth, a success partially credited to the one-child policy.”

However, she added, “China’s rapid economic growth has had little to do with its population-planning curbs. Indeed, the policy is imperiling future growth because it rapidly created a population that is too old, too male, and, quite possibly, too few. More people, not less, was one of the reasons for China’s boom…. China’s rapid economic rise had more to do with Beijing’s moves to encourage foreign investment and private entrepreneurship than a quota on babies.”

It is also now clear that we can “support population control without embracing anything so brutal as a one-child policy,” Fong said.

Early this year, The Wall Street Journal reported:

“The number of newborns in China fell for a fifth straight year to the lowest in modern Chinese history, despite Beijing’s increasing emphasis on encouraging births….

“China, which just a few short years ago harshly restricted how many children couples could have, now struggles to persuade them to have more. Since Beijing last year said all couples could have three children, local governments have tried measures including cash rewards and longer maternity leaves to boost births. To facilitate marriages, local officials have organized matchmaking events and discouraged the use of dowries.

“These efforts haven’t seemed to yield significant results. China’s marriage registrations, after declining sharply in 2020, continued to drop over the first nine months of last year, the latest official data showed.”

I believe in experts in specific professions: medical doctors, mechanics, computer technicians, plumbers, educators, economists, lawyers, etc. I also believe that you are the best expert on yourself.

But when it comes to matters of public policies that will affect everyone, I tend to be skeptical of what “experts” say, especially if their proposed “solutions” are one-size-fits-all and involve “sacrifices” on our part, enduring inconveniences and paying more for less while embracing “hardships” that they say are “necessary” for the sake of the “future.”

Sounds great. Please go away now.

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com