MANY concerned citizens believe that good government is an achievable goal. All we need, they say, are intelligent voters who will elect competent leaders.

This reminds me of an apocryphal story involving the great French sculptor Rodin. When asked how to sculpt an elephant, he supposedly replied, “Simple. Take a block of marble and remove everything that isn’t an elephant.”

However, governance and politics are not so easily molded, which is one of the central insights of “The Federalist Papers.”

Whenever we propose “badly needed” reforms or changes we seem to forget that 1) a majority of voters must support them; 2) they must elect like-minded politicians; 3) who must enact these reforms; 4) implement them; and 5) deal with the immediate effects of these measures, their immediate “impact,” as they say, on voters, while bracing for unintended and/or unforeseen consequences.

In the case of the CNMI government, its main problem — its bloated size — is more of a feature than a bug. This creaking government apparatus was inherited by Commonwealth leaders from their Trust Territory predecessors. Another “legacy” from the TT era was the deep-seated belief — if not conviction — that government is the employer of choice and the source of all that is good and true, including free healthcare, scholarships, and low-cost utilities.

As the Washington Post reported in 1978, “Thirty-one years of American trusteeship…has created a society dependent on government jobs and benefits, island welfare states whose people are so inundated with free handouts that they are abandoning even those elemental enterprises — fishing and farming — that they had developed before the Americans came. ‘We’ve smothered them,’ agrees a veteran U.S. administrator with the Trust Territory government, ‘and it will take them a long time to come out from under this blanket.’ ”

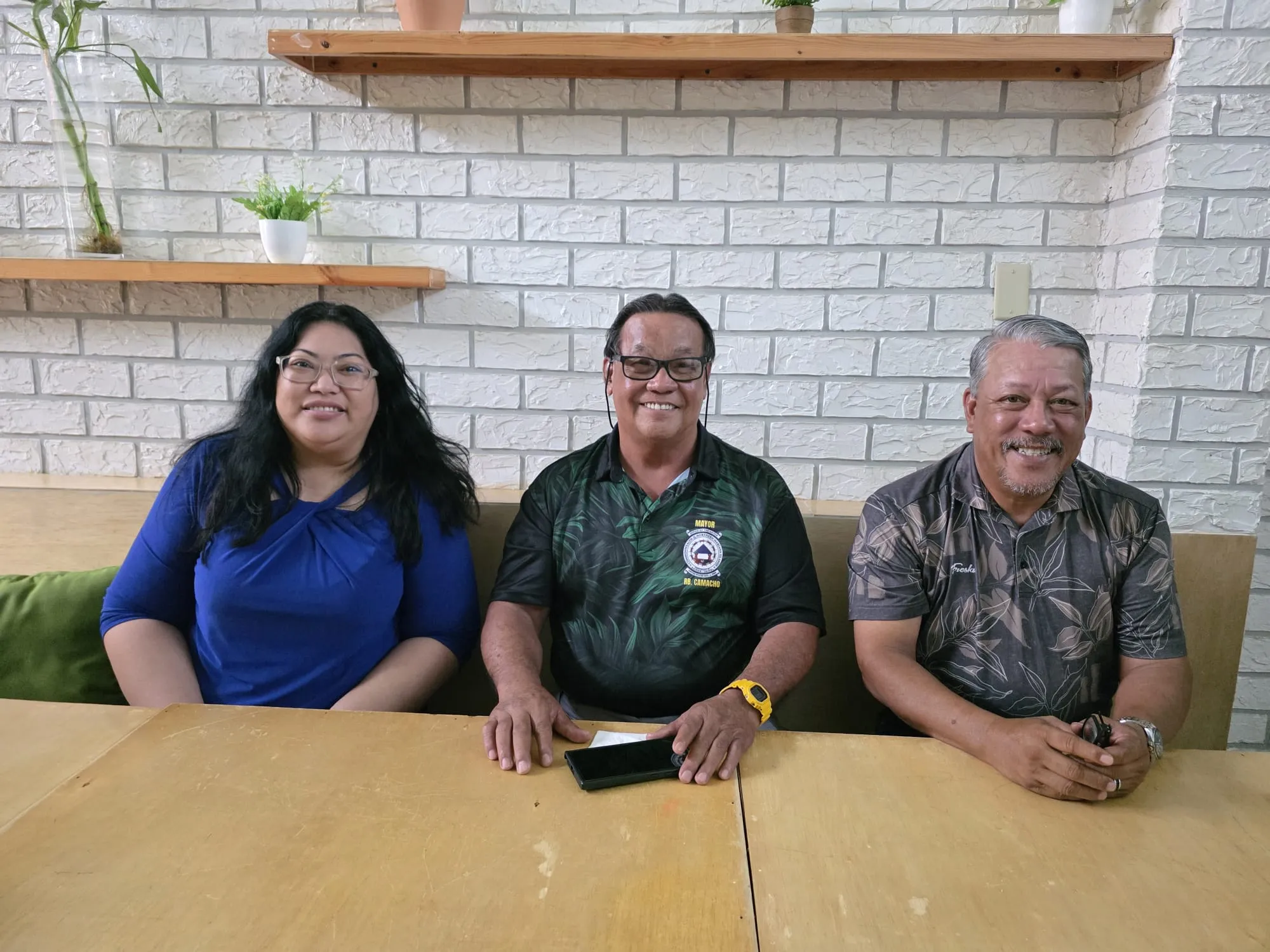

In 1994, local businessman Efrain Camacho said “the Trust Territory mentality should no longer reign in everyone’s mind. This mindset limits productivity and accountability…because the person has the belief that the government will always be there to help.”

That mindset is difficult to shake.

To be sure, anyone can propose reform measures. Politicians running for office often talk about them. However, once elected, they quickly realize that such reforms would impose hardships on a significant portion of the electorate — who will, in turn, vote them out in the next election.

Hence, any talk of “creating a better future” contradicts the realities of democracy. For many politicians and voters, the future is the next election, and voters are known to change their minds often.

Our would-be saviors

Ultimately, what many reformists seek often clashes with the pluralism guaranteed by constitutional democracy. To them, further discussion is unnecessary. However, this assumes that all of us — or at least a vast majority — are in perfect agreement with them and will remain so for the long haul. But not even the most bloodthirsty totalitarian regimes have managed to achieve that.

As Bryan Cheung of the London School of Economics and Political Science noted recently, “the reality of democratic politics is one of constant contestation, where consensus is rare and transient.” Competing interests and conflicting priorities, he added, make it virtually impossible to sustain the focus that “mission-oriented” reformists demand. Not surprisingly, our would-be saviors prefer a “climate of conformity” in which “alternative perspectives are delegitimized, and dissenting voices are cast as barriers to progress.” For some reformists, resistance should be framed “as betrayal rather than legitimate debate.”

This, however, flies in the face of the democratic rights that a democratic government is mandated to uphold.

All of this, to be sure, is exasperating for those who are eager to “solve” societal and governance “problems.” They want a democracy that “works.” However, democracy does not guarantee solutions. What it does ensure is a system where everyone’s voice can be heard — without resorting to violence or imposing one’s vision on the rest of us, whether we like it or not.

Some may find that these safeguards are not enough, and perhaps they’re right, but what we have right now is an unheard-of luxury in many other countries.

You say you disagree.

That’s the spirit.

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com