EVEN if your grade school textbooks showed you pictures of the men — all men — who were busy plotting and scheming to create what was to be the United States of America, you might find it hard to conceive of the stress under which these now venerated founders operated.

Even in the best of times, those living and working to create the country-to-be experienced both physical and mental strains, meeting secretly in dimly lit tavern backrooms and other secluded spots to avoid detection by the authorities.

The founders weren’t elderly for the most part, but the hard times they endured had an impact as they aged. The vision of many suffered, a mild description of potential blindness due to cataracts, but the offerings of the medicine of the day were severely limited.

Given that some 250 years later the eyes of more than 24 million Americans over 40 are estimated to be affected by cataracts, it is not surprising that back in the 1700s, a British-trained surgeon capable of performing the cataract surgery of that time would do well in Boston. Dr. Benjamin Church had such qualifications.

The British military men in charge of maintaining the colonies for London were well aware of the dissatisfaction of their subjects which was displayed in various incidents including what became known as the Boston Massacre in 1770 in which British soldiers opened fire on a crowd of sailors killing five. The 1773 Boston Harbor Tea Party tax protest was another.

The military rulers missed few opportunities to gather intelligence on the unfolding events, cultivating spies to report on those working against their mother country.

My ancestor, Dr. Benjamin Church, descendant of arrivals on the 1620 Mayflower voyage and prominent members of the colonial elite, was able to attract many patients, including founder John Adams, later to be second president of the United States. Adams was well known to suffer from various eye maladies.

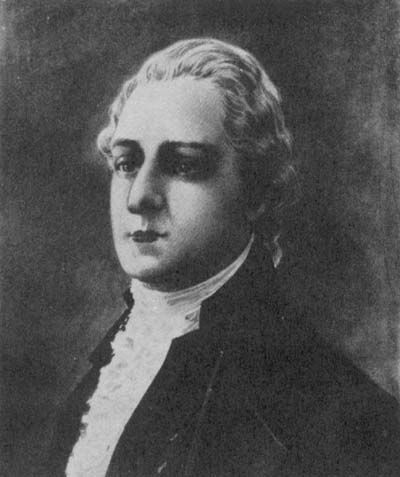

Founder Benjamin Franklin suffered from myopia and presbyopia of his eyes, but the bifocal lens which he invented was reportedly able to compensate for some of the symptoms of both.

It’s unclear exactly what treatments Dr. Church could offer his patients in the 1770s, but medical and other efforts to overcome cataracts stretch far back into antiquity and have evolved into a procedure that can and is often done in 10-15 minutes, one of the most common and safe surgeries in all of medicine.

Guam ophthalmologist Dr. Peter Lombard: “My guess is that ‘couching’ was performed in colonial America by a small handful of eye surgeons and was probably the only technique used in the first half of the [18th] century.”

Another account describes “couching”: “The surgeon would introduce a sharp needle into the eye and force the lens to sink into the vitreous to remove it from the visual field.” And that’s without modern anesthetics, technology or sterile procedures.

“English surgeon Samuel Sharp is credited with performing the first successful intracapsular cataract extraction in 1753,” Dr. Lombard said, “in which he removed the entire lens along with the surrounding capsule.” Sharp’s technique was considered a significant advance at the time.”

By another account, (Dr. Sharp) then “used his thumb to expel the cataract from the eye.”

None of these practices restored vision 100% and the consequences when they went wrong could be terrible.

Whatever techniques he used in his medical practice, Dr. Church worked his way into the highest of revolutionary councils, while leaving some observers suspicious.

He performed the autopsy of Crispus Attucks in 1770 when he became known to history as the first American killed in the Revolutionary War, describing it later as a “Bloody Tragedy.”

On the other hand, some parties viewed him as a secret Tory (British) sympathizer, others as an American Patriot. As a member of the Provincial Congress, he was assigned various positions and duties, including service as (effectively) the first U.S. Surgeon General.

With the war underway in 1775, Americans such as Paul Revere wondered how British Governor and General Thomas Gage seemed to know precisely what they were up to behind the scenes.

Revere wrote later: “We held our meetings at the Green-Dragon Tavern. We were so carefull that our meetings should be kept Secret; that every time we met, every person swore upon the Bible, that they would not discover any of our transactions, But to Messrs. HANCOCK, ADAMS, Doctors WARREN, CHURCH and one or two more.”

A cipher-coded letter intended to be passed to a British officer through a former mistress of Dr. Church revealed information about American forces and fortifications and made it clear his allegiance was to the crown rather than the colonials. Passed into American hands, it was de-ciphered.

A court of inquiry chaired by General George Washington concluded that this was “criminal correspondence,” but it wasn’t until the 20th century that files of General Gage confirmed that Dr. Church had in fact regularly served the British side as a spy.

Apparently because of some doubt about circumstances, Dr. Church escaped such typical wartime penalties for treason as hanging, serving two brief prison stints before being banished by law from Massachusetts in 1778. The ship on which he embarked for the Caribbean as the war raged on, was never heard from again.

A former Saipan resident, the author is a veteran editor/writer who lives in Guam.

Benjamin Franklin

Dr. Benjamin Church

John Quincy Adams