LAST week, the Wall Street Journal published a front-page report titled, “Officials Boost Firms —And Own Interests”; and, no, it wasn’t about the CNMI’s BOOST program.

According to the Journal:

“In 2021, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. deliberated over whether to tap Microsoft Corp. as its primary cloud provider. Three key officials involved in the discussions, or their family members, owned shares in Microsoft, including the deputy chief information officer who pushed to pick the company.

“By early 2022, Microsoft had become the agency’s primary cloud platform.”

At the U.S. Export-Import Bank, the Journal added, “an official used her government position to help her husband’s lobbying organization, which was seeking to block or delay a policy change proposed by the Trump administration.”

The Journal said it has “documented a sweeping pattern of executive-branch officials owning and trading stock in companies affected by the work of their agencies. Further reporting shows some not only invested in firms their agencies oversaw but personally worked on significant matters affecting those companies….

“The examples identified by the Journal are ‘very brazen conflicts of interest,’ said Craig Holman, a government-ethics expert at the nonpartisan advocacy group Public Citizen. U.S. law prohibits officials from working ‘personally and substantially’ on any matters in which they have a significant financial stake.”

Now the U.S. is considered the world’s oldest democracy with a constitution in effect since 1788. Over so many years, America’s politicians and government officials at all levels have become familiar with how democratic politics works in theory — and in practice. They would not have been surprised by the Journal’s latest “exposé.”

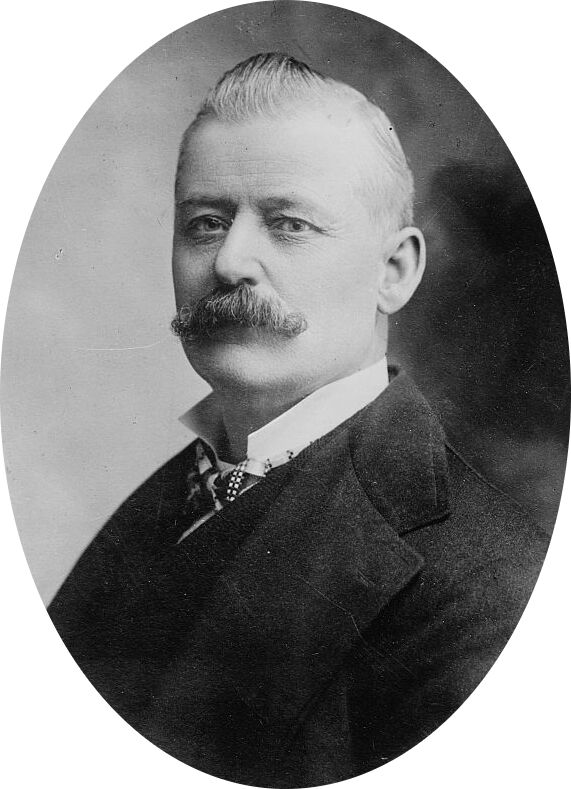

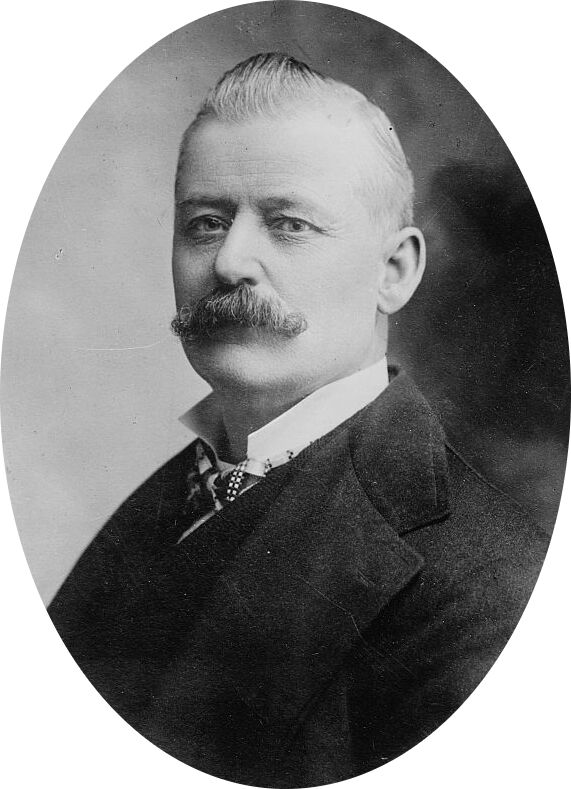

George Washington Plunkitt (1842-1924) of New York was one of those pols/government officials. A state legislator and a leader of the Democratic Party’s (in)famous political machine, Tammany Hall, Plunkitt was a grandmaster of politics. His “Very Plain Talks on Very Practical Politics” was first published in 1905, and is still available in paperback, on Kindle or online. What many of us would end up learning after decades of observing and studying politics is all there in that thin volume (less than 100 pages).

Arthur Mann, in his introduction to the 1963 paperback edition of Plunkitt’s book, asks,

“Do you want to break into politics? Plunkitt tells you how: don’t go to college and stuff your head with rubbish, but get out among your neighbors and relatives and round up a few votes that you can call your own…. Why don’t reformers last in politics? Because they’re amateurs…and there’s nothing like a pro” in politics.

Plunkitt’s advice to aspiring politicians is timeless. To hold a district, he says, “you must study human nature and act accordin’…. [Y]ou have to go among the people, see them and be seen. I know every man, woman and child in [my] district, except them that’s been born this summer — and I know some of them, too. I know what they like and what they don’t like, what they are strong at and what they are weak in, and I reach them by approachin’ at the right side…. I don’t trouble them with political arguments…. No, I don’t send them campaign literature. That’s rot. People can get all the political stuff they want to read — and a good deal more, too — in the papers. Who reads speeches…anyway? It’s bad enough to listen to them…. What tells in holdin’ your grip on your district is to go right down among the poor families and help them in the different ways they need help…. It’s philanthropy, but it’s politics, too — mighty good politics…. The poor are the most grateful people in the world and, let me tell you, they have more friends in their neighborhoods than the rich have in theirs…. Another thing, I can always get a job for a deservin’ man….” That is, a voter.

For Plunkitt, “there’s no crime as mean as ingratitude in politics.” He said “the ingrate in politics never flourishes long…. The politicians who make a lastin’ success in politics are the men who are always loyal to their friends, even up to the gates of State prison….”

Plunkitt also believed that a successful politician does not drink. No one, he said, can manage a district long if he drinks. “He’s got to have a clear head all the time…. The district leader makes a business of politics, gets his livin’ out of it, and, in order to succeed, he’s got to keep sober just like in any other business.”

Plunkitt admitted that he had “made a fortune out of [politics], and I’m gettin’ richer everyday but I’ve not gone in for dishonest graft” which involves using one’s political power to engage in illegal activities such as bribery or embezzlement. No sir. Plunkitt was into “honest graft”:

“My party’s in power in the city, and it’s goin’ to undertake a lot of public improvements. Well, I’m tipped off, say, that they’re going to lay out a new park at a certain place.

“I see my opportunity and I take it. I go to that place and I buy up all the land I can in the neighborhood. Then the board of this or that makes its plan public, and there is a rush to get my land, which nobody cared particular for before.

“Ain’t it perfectly honest to charge a good price and make a profit on my investment and foresight? Of course, it is. Well, that’s honest graft.”

According to Arthur Mann, when Plunkitt died in 1924, The Nation, “one of the outstanding journals of advanced opinion, commemorated [him] as ‘one of the wisest men in American politics….’ He understood that in politics, ‘honesty doesn’t matter; efficiency doesn’t matter; progressive vision doesn’t matter. What matters is the chance of a better job, a better price for wheat, better business conditions.”

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com

George Washington Plunkitt