SENDAI CITY, Japan — After several tsunami evacuation drills and community disaster planning, the students, faculty, and administration of Arahama Elementary School in Sendai City knew just what to do when it was hit by the catastrophic earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011.

Seventy-one of the ninety-one students were on campus when the earthquake shook northeastern Japan. Takao Kawamura, the principal at the time, grabbed his megaphone, knowing full well that the school’s public address system had been knocked out. He immediately instructed teachers to gather the children and to put their disaster preparedness drills into action.

After the shaking stopped, everyone made their way to the fourth floor of the building, just like they had practiced during their drills. Luckily, a decision had been made a few years earlier to herd people to the fourth floor instead of the gymnasium at ground level. The students and residents who had fled their homes would later make their way to the roof as the tsunami rose around nine feet, “like a black mountain,” as one community member later described it.

Signs were posted all over the school, and school drills were in place. One community leader said that if anyone had evacuated to the gymnasium, they would have died. Sure enough, when the tsunami came, the gymnasium was so severely damaged, it eventually had to be demolished.

One might say that it was the school’s proactiveness that saved the lives of the 71 students, their teachers, the school administration, as well as their community members who sought safety at the school.

“We should prepare ourselves as soon as we can,” the former principal said in a documentary, recalling that fateful day. 320 people from the surrounding area survived by seeking refuge on the school’s upper levels.

It would be several hours before they would be rescued one by one, lifted up to a helicopter by volunteer firefighters, and transported to a shelter further inland, away from the wreckage. While waiting to be rescued, they listened to the death toll announced on the radio. In all, 190 residents in Arahama lost their lives. “If only we all could have done something more, myself included,” said Kawamura.

Today, the school, stained by black waters and battered by raging waters, has no students. But the building has been preserved and opened to the public as a reminder of the disaster and the importance of being prepared.

Local resident and guide Tomoyuki Takayama pointed out that loud speakers have been placed on the roof to blare disaster warnings over a one-kilometer radius. In addition, work has been done to fortify Arahama’s dikes and public spaces, to help blunt the force of future tsunamis.

Houses once lined the streets of Arahama, which lies along the ocean. Now, no one is allowed to live between the east dike and the main road. A second dike has been built further inland, serving as a secondary tsunami barrier. And there are now three raised evacuation shelters between the main road and the west dike. They have been designed so that people can flee to higher ground within 45 minutes after an earthquake.

Survivors of the March 11 disaster who hail from Arahama occasionally come to visit the school. However, there are those who still find it traumatizing to spend time in the area. Takayama shared that two of his friends, a couple who lost their two-year-old child in the tsunami, have yet to visit the memorial built in honor of the victims. He said that it is important to preserve the ruined school, so that people remember — and better prepare for future disasters.

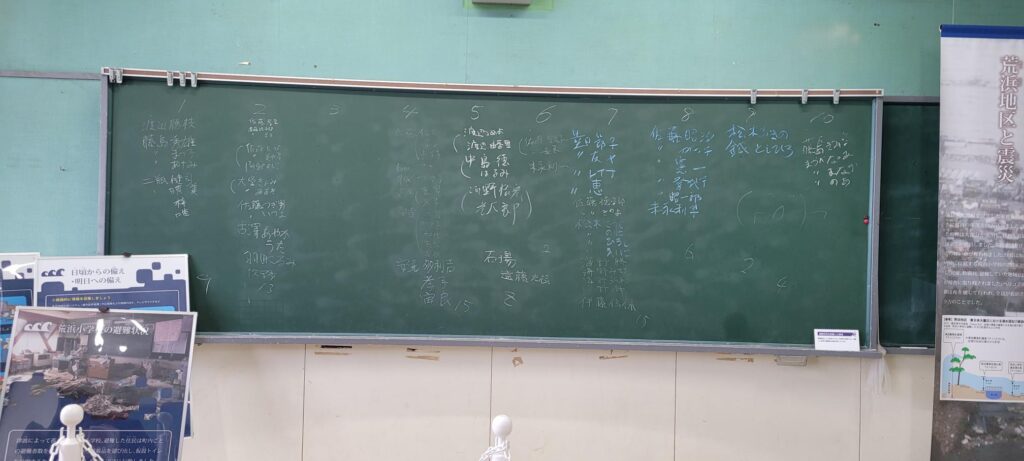

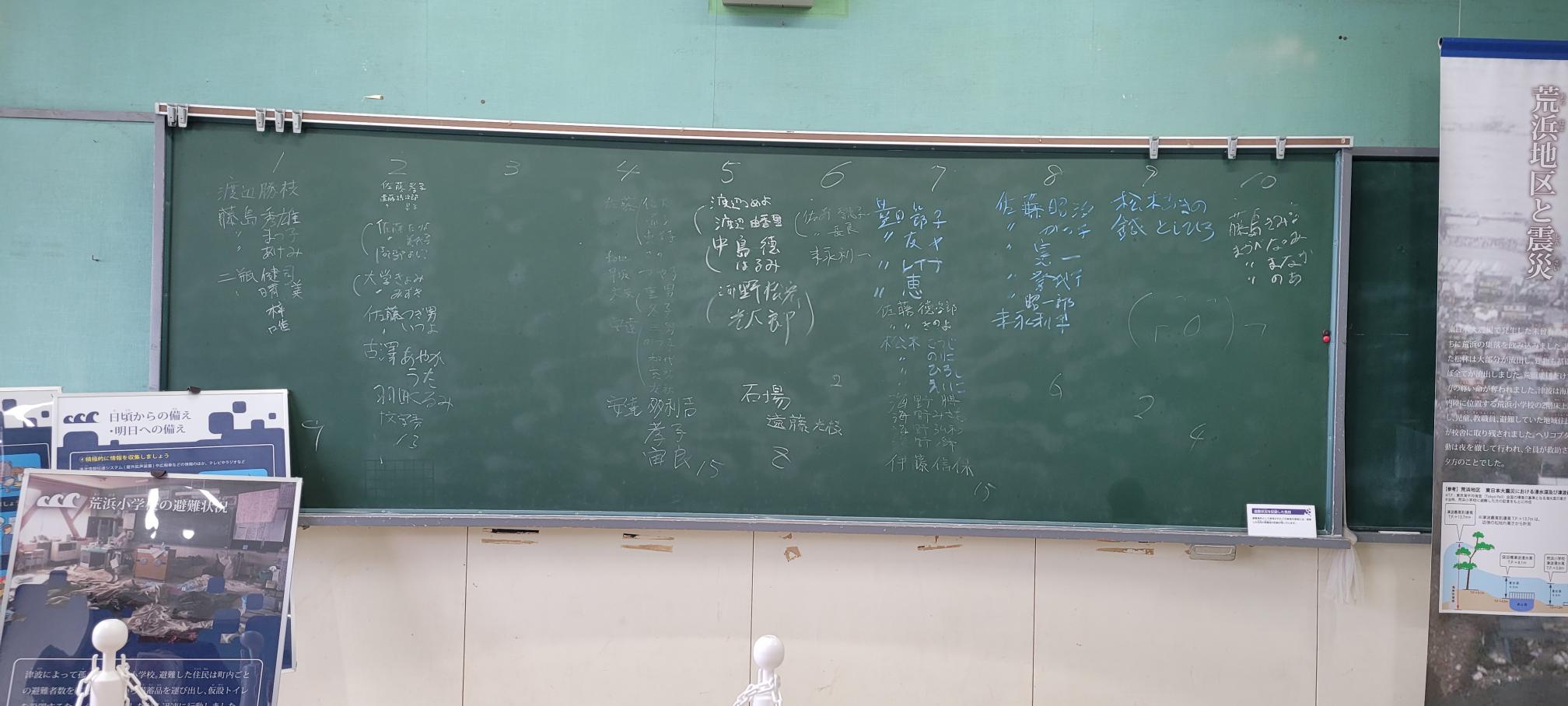

Written on a chalkboard in an Arahama Elementary School classroom are the names of survivors who sought refuge there on March 11, 2011.