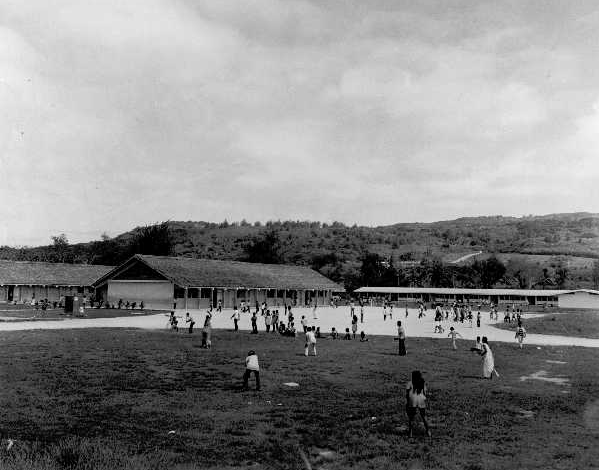

Garapan Elementary School, 1976

STUDYING history lets you step back and see today’s pressing issues in perspective. For example, education. In the CNMI, education is a smashing success, but it seems that few of us realize this. Not a lot of us are also aware that under direct U.S. rule during the Trust Territory days, the NMI and the other TT islands were stuck in an economic limbo. As E.J. Kahn Jr. noted in his 1966 book, “A Reporter in Micronesia,” while other war-torn cities had already risen from their ashes, “Garapan is still nothing. Just about all that remains of its former glory is a larger-than-life-size bronze statue of the founder of the sugar-cane industry there. Now bullet-riddled, he stands forlornly in what was once a manicured botanical garden, but now is a tangle of undergrowth….” Prior to World War II, he added, Garapan was the “pride of Saipan” with modern amenities. Kahn said 20 years after the war, the Japanese era was known among islanders as “The Concrete Period,” while the American Period was “The Corrugated Tin Period.”

In 1992, Gov. Larry Guerrero reminded U.S. lawmakers that Saipan was one of the last major battlefields of World War II to enter the reconstruction phase. “This,” he added, “did not occur until the early eighties,” when the NMI was already a U.S. Commonwealth.

According to the 1966 Nathan Report — which was commissioned by the U.S. government — the Trust Territory government was operating at the time with a total expenditure ceiling of…$6.5 million. That’s equivalent to about $59.8 million today. We’re talking about a government that was administering the NMI, Palau, the Marshall Islands, and what is now known as the FSM. The TT government’s budget, as the Nathan Report would put it, was “barely adequate to ‘keep house.’ ” Not surprisingly, minimum “facilities and services existed for transportation, communications, education, hospitals, health, sanitation, and public works.” At the time, there were only a few islanders “provided with secondary and some college education in Guam, Honolulu, and the United States….”

Kahn said it was much worse in the 1950s when “the most money ever allocated to the Trust Territory by [the U.S.] Congress was just over a million dollars a year, and since a good deal of that had to go into subsidizing transportation, making ends meet was not easy. But it was still American policy then to move slowly in Micronesia, and everything just sort of limped along. Most of the money that was spent was spent on facilities for the Americans who were out there to spend the money.”

As for the U.S. Naval administrators of the islands shortly after World War II, Kahn said they believed that “we should try not to alter the age-old pattern of native life, and that [islanders] would fare best if they were left to their own devices and kept apart from Western customs — the ‘zoo theory’ of administration, as anthropologists sometimes call it. One zoophilic Navy admiral who got to know the natives well declared… ‘for mercy’s sake let them alone in their happiness!’ ”

In 1958, Kahn said, the entire Trust Territory had no high school. In 1962, it had a single one. He also noted the islanders’ “enthusiasm for education….”

Starting in 1978, as a self-governing U.S. Commonwealth, the Northern Marianas embarked on an ambitious education policy “in spite of a limited, strained budget,” as the CNMI’s first governor, Dr. Carlos S. Camacho, would put it.

Since then, the CNMI has implemented scholarship programs, built more schools, opened its own college, trained and hired more local educators, and is producing, each year, hundreds of high school graduates who are expected to thrive if not excel academically in higher learning institutions in the U.S., including Ivy League universities. Many CNMI leaders and officials are well-educated, and most local departments and agencies are headed and staffed by educated local men and women.

Today, only bad health or extreme misfortune could prevent a local resident from going to high school and then to college — or trade school. There are also programs to accommodate adults who dropped out of school when they were younger. And there are other programs — local and federal — that provide other assistance to students, including those who want to pursue postgraduate degrees.

Apparently, many of us have taken for granted this remarkable state of affairs in education, to the point that few of us see the connection between a highly educated population and the persistent shortage of workers in certain jobs.

The local population remains small, and many residents have — or are earning — college degrees, yet everyone seems “surprised” by the perennial shortages in construction, caregiving, service, and other non-college-degree jobs, with politicians blaming a supposed “lack of training opportunities.”

But that’s another story.

Send feedback to editor@mvariety.com