ALTHOUGH the Japanese government had tendered their offer to surrender on Aug. 10, according to the Potsdam Declaration, the terms were not satisfactory to the American leadership. The Japanese offer had accepted Unconditional Surrender, but “with the understanding that said declaration does not comprise any demand which prejudices the prerogatives of His Majesty as a Sovereign Ruler.” This appeared, at first, to contradict the concept of Unconditional Surrender.

Secretary of State James Byrnes created the following response for President Truman’s response: “From the moment of surrender, the authority of the Emperor and the Japanese Government to rule the state shall be subject to the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, who will take such steps as he deems proper to effectuate the surrender terms. The Emperor will be required to authorize and ensure the signature by the Government of Japan and the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters of the surrender terms necessary to carry out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration…. The ultimate form of government of Japan shall, in accordance with the Potsdam Declaration, be established by the freely expressed will of the Japanese people.” (Farrell, “Seabees and Superforts at War,” p. 457-458).

When the Japanese had not responded to this message by Aug. 13, Truman ordered Nimitz and LeMay to resume “unremitting pressure.” LeMay dispatched full-force missions to targets across Japan on August 14. Of the 828 B-229s launched, 749 reached their targets, along with 186 fighter escorts based on Iwo Jima, returning to their respective bases that evening (see Smith, James and Malcolm McConnell. “The Last Mission: The Secret History of World War II’s Final Battle.” New York: Broadway Books, 2002, p. 265).

Before daylight on the morning of Aug. 15, Admiral Halsey sent a hundred naval aviators from this carrier fleet offshore to targets on Honshu.

In the meantime, the Emperor had worked with his staff to create an Imperial Rescript announcing his decision to surrender to the people of Japan. He signed the rescript at 8:30 p.m. (“Japan’s Longest Day.” Compiled by the Pacific War Research Society. Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco: Kodansha International, 1968, p. 166). He recorded the rescript onto wax discs (records) to be played at noon on Aug. 15.

On the evening of Aug. 14, a group of hot-headed officers led an attack on the Imperial Palace to find the discs and destroy them before they could be played. Because of the Aug. 14 mission, the lights had been turned off in Tokyo, including at the Imperial Palace. This helped prevent the rebels from finding the discs.

General Anami, commander-in-chief, Imperial Japanese Army, committed suicide that evening.

Just before 6 p.m. in Washington, D.C., President Truman received a copy of the message from Japan announcing the Emperor’s decision to surrender:

“1. His Majesty the Emperor has issued an Imperial Rescript regarding acceptance of the provision of the Potsdam Declaration.

“2. His Majesty the Emperor is prepared to authorize and ensure the signature by his Government and the Imperial General Headquarters of the necessary terms for carrying out the provisions of the Potsdam Declaration. His Majesty is also prepared to issue his commands to all the military, naval, and air authorities of Japan and all the forces under their control, wherever located, to cease active operations, to surrender arms, and to issue each other orders as may be required by the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces for the execution of the above-mentioned terms.”

Truman announced the message to the media at 7 p.m. Eastern War Time, Aug. 14 (Aug. 15 Guam time) in the Oval Office (“Japan’s Longest Day,” p. 176).

The rescript was played over the air throughout Japan at noon Aug. 15, and simultaneously broadcast on military bases on Saipan, Tinian and Guam.

“Let the entire nation continue as one family from generation to generation, ever firm in its faith of the imperishableness of its divine land, and mindful of its heavy burden of responsibilities, and the long road before it. Unite your total strength to be devoted to the construction for the future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude; foster nobility of spirit, and work with resolution so as ye may enhance the innate glory of the Imperial State and keep pace with the progress of the world.” (“Tinian and The Bomb,” p. 404).

Stalin had been hugely upset when he received word of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima on Aug. 7. He immediately ordered the Russian invasion of Hokkaido, the northernmost island of the four Japanese Home Islands. Then he read about Truman announcing Hirohito’s decision to accept the Potsdam Declaration. He couldn’t stand the idea of Russia being cut out of the spoils of war in Japan.

On Aug. 16, Marshal Joseph Stalin wrote to President Harry Truman suggesting that the area of Soviet occupation should include the northern half of Hokkaido Island:

“On the line leading from the city of Kushiro on the eastern coast of the island to the city of Rumoi on the western coast of the island, including the named cities to the northern half of the island.

“Russian public opinion would be gravely offended if the Russian troops had no occupation area in any part of the territory of Japan.”

However, Truman had long before decided Japan would not be divided as Germany had. He flatly rejected Stalin’s request:

“Regarding your suggestion as to the surrender of Japanese forces in the island of Hokkaido to Soviet forces, it is my intention and arrangements have been made for the surrender of Japanese forces on all the islands of Japan proper, Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu to General MacArthur.” (Farrell, “Tinian and The Bomb,” p. 416-417).

Stalin decided to accept the American position on the surrender of Japan, for two reasons. America had the atomic bomb, and he needed to focus on the gains he could make in Europe. The Cold War had begun.

All that remained was the surrender ceremony, providing food to the prisoner-of-war camps in Japan, and occupying Japan.

President Harry Truman announces the surrender of Japan to the media in the Oval Office.

Secretary of State James F. Byrnes

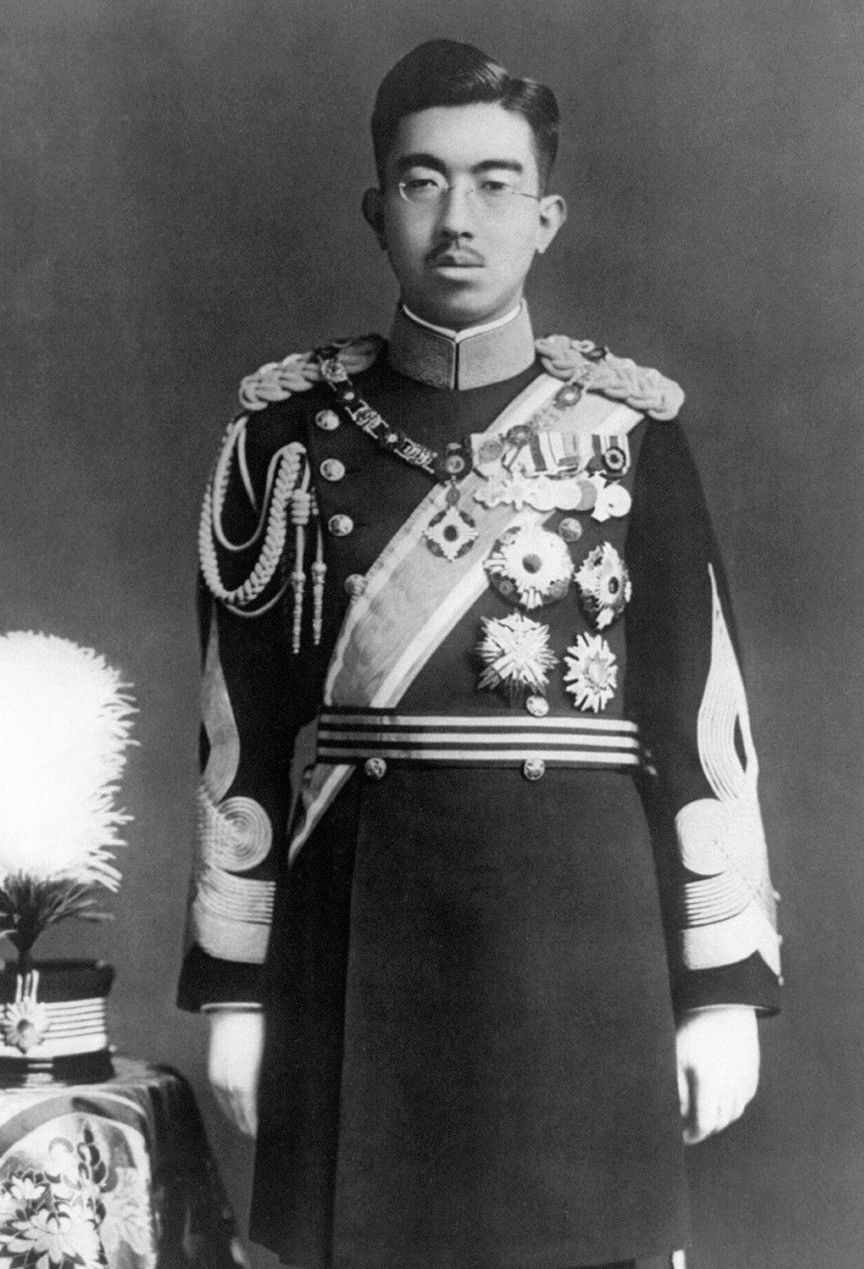

Emperor Hirohito

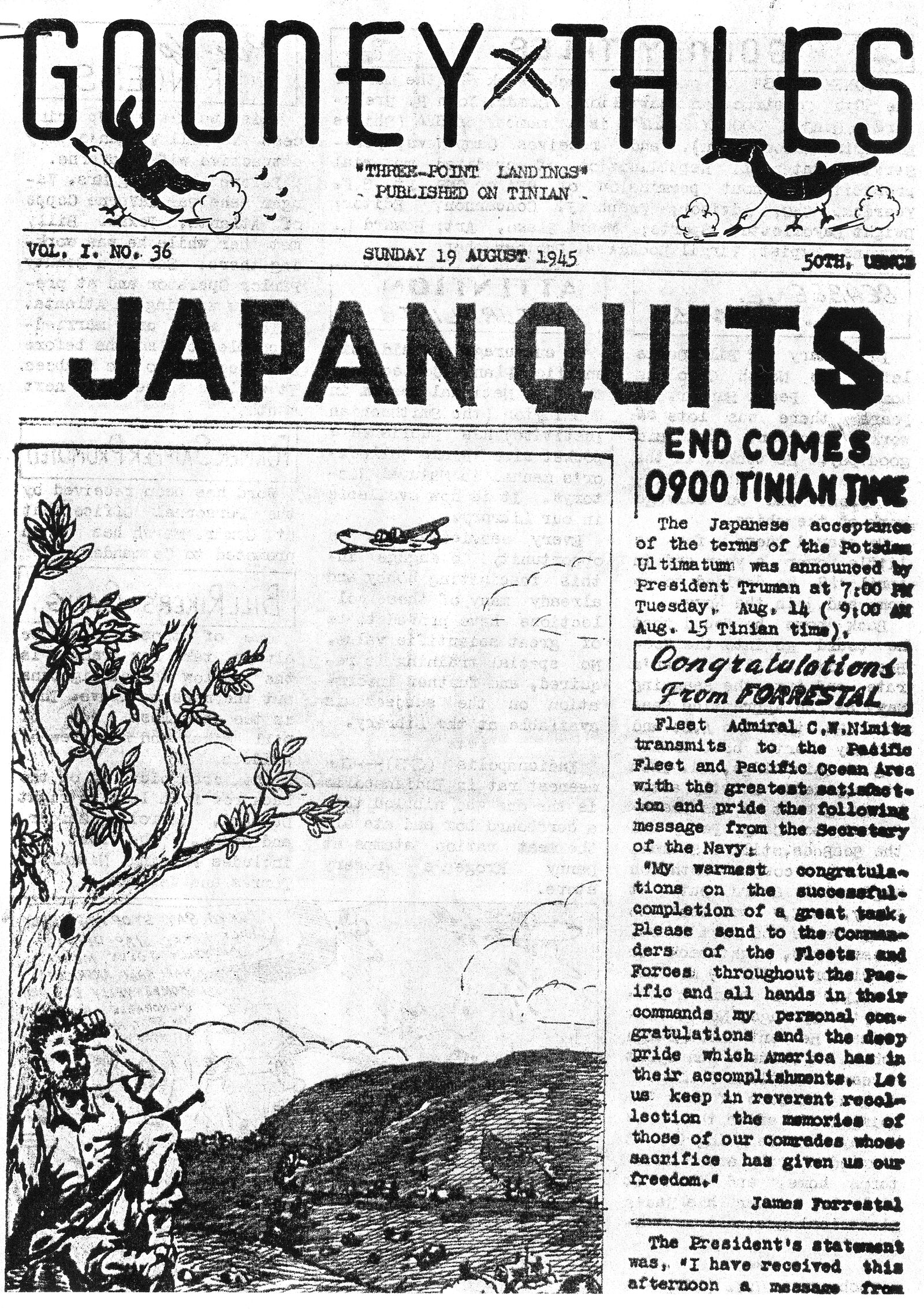

Gooney Tales, Vol. 1, No. 36

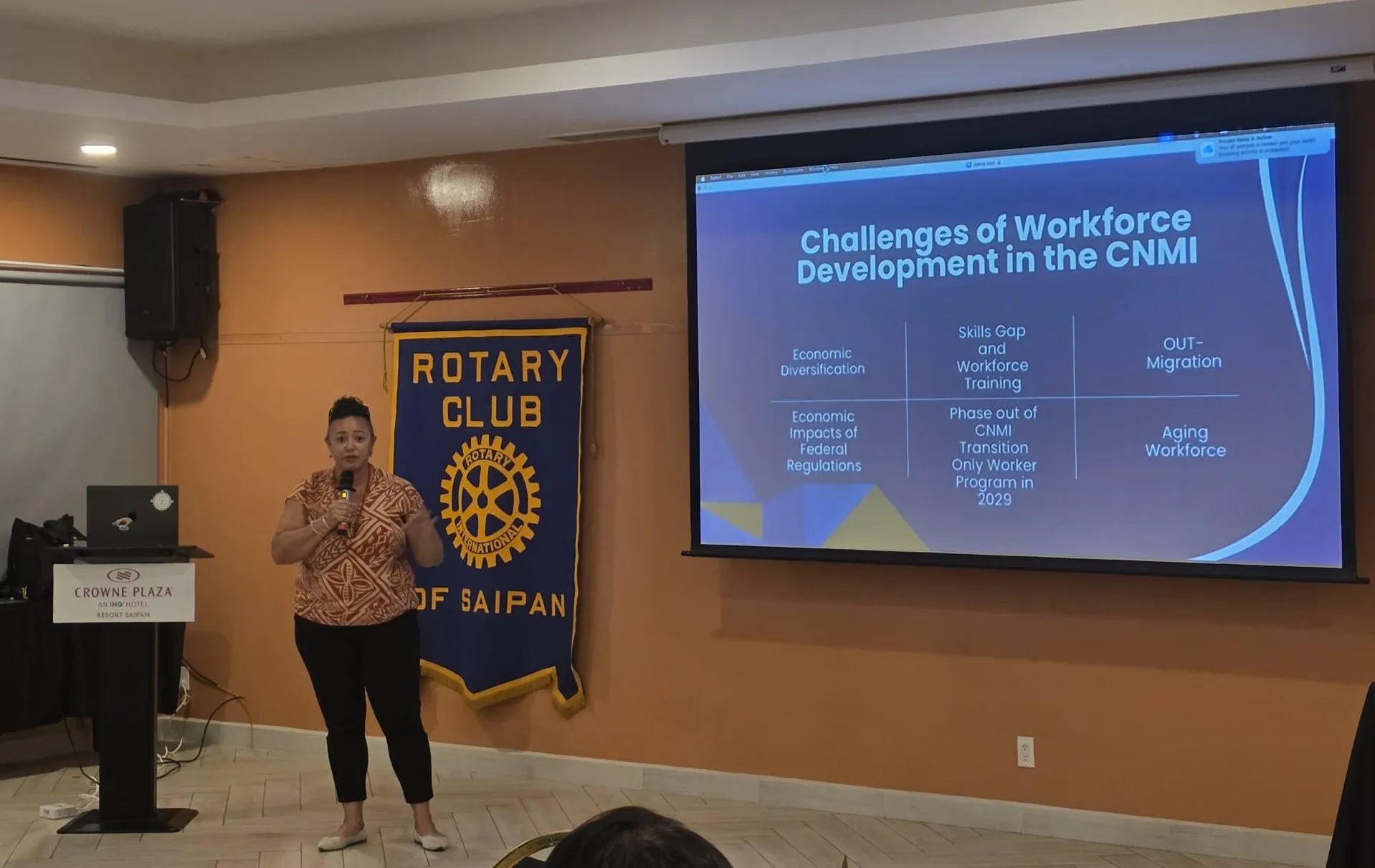

Saipan Beacon