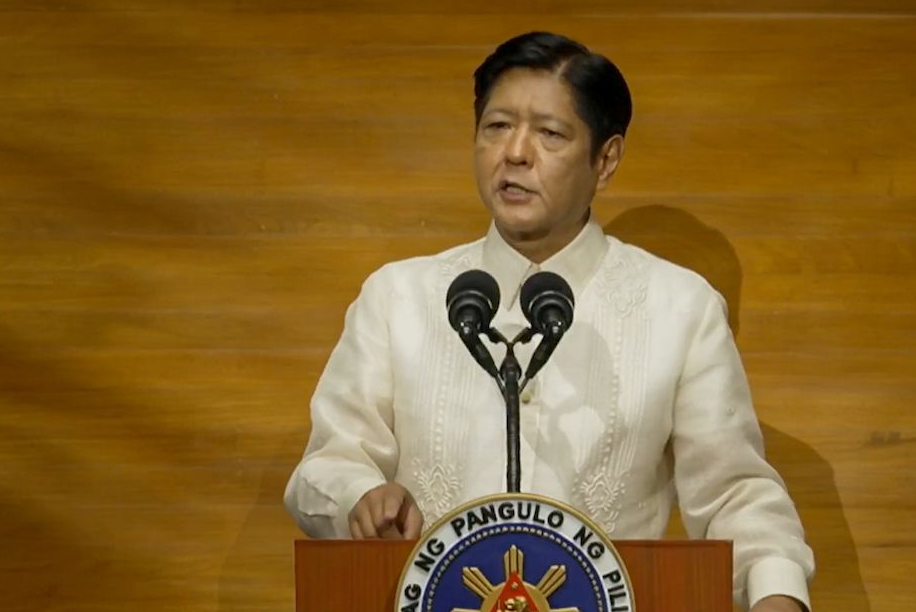

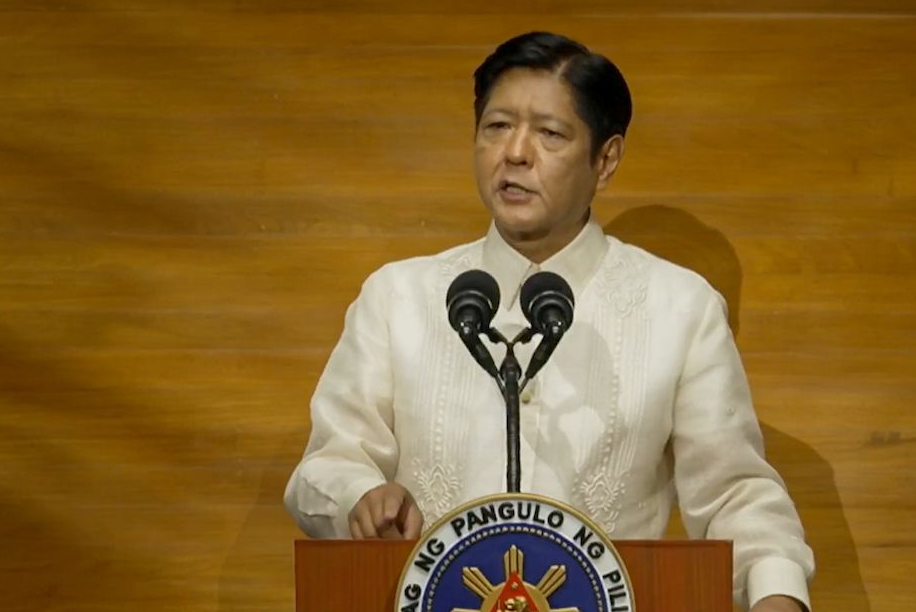

ALMOST as soon as he arrived from trade negotiations that resulted in the imposition of as much as 19% tariffs on Philippine exports to the United States against “reciprocal” 0% inbound tariffs on imported American goods, Philippine President Ferdinand R. Marcos immediately got to work in crafting his State of the Nation Address or SONA.

Most people forget their nightmares as soon as they wake up. The post-tariff deal SONA was no different.

There is, however, a slew of AI-generated summaries digesting the kitschy evening-gown exercise mandated by Article VII, Section 23 of the 1987 Constitution, ordering a presidential report to Congress on the country’s state of affairs. Ideally, it would have highlighted the impact on the economy of the tariff deal. It did not. Not one word.

Patterned after the United States’ own the SONA has over time expanded beyond its primary purpose of being a check and balances democratic doodad in our toolbox.

After winning back our democracy in 1986, the pre-SONA protocols included a survey of present programs and prospective plans curated by the Presidential Legislative Liaison Office. This was soon institutionalized through the Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Council, especially critical where the legislature did not always march in lockstep with the administration.

The process took as long as two months, and one unspoken objective was to avoid unnecessary friction between two branches of government. This was critical given a secondary objective within the SONA in a charged milieu typically a product of partisanship and petulant political alliances.

Beyond a mere presidential reportage, the SONA was to deliver a legislative message to Congress as to what they were to focus on in line with the vision of the president and the very specific goals he wanted to achieve within the next twelve months. Necessarily, this required preparations, planning, strategic thinking and close coordination with the executive’s budget department as any undertaking needed funding. And since funding was limited to the revenues that the plans and programs that the president envisions could generate, the Budget Department’s proposed General Appropriations Act was an important first step.

Admittedly, such was a circuitous if not labyrinthine undertaking where limitations are set and overpower most of the ambitions and hyperbole generated by an hour’s speech.

Since the dark dictatorship years, we cannot recall one SONA where these two objectives were realized save perhaps for a couple of rare instances during the presidency of Corazon C. Aquino and immediately thereafter, when Fidel V. Ramos succeeded her.

It helped tremendously that the stark differences of classic Grecian Evil versus Good morality plays characterized our transition to democracy under Aquino and immediately thereafter, the follow-up towards government efficiency and competence that characterized the Ramos agenda.

It bears stating that in its twilight, the dictatorship had plunged the Philippine economy deep in debt that international creditor moratorium was needed to avoid total bankruptcy.

But what if conditions, whether good or evil, were set in a continuum? What if a previous evil simply predicated another, or worse, took whatever was gained post-dictatorship and again plunged the economy into debt, reinstituting a culture of failed governance and aggravated matters? The quick answer is a situation that leaves matters unresolved. Where the SONA is concerned, critical matters would remain un-addressed.

On the virtual eve of the SONA the most bannered controversy was the ballyhooed “tough” tariff negotiations between the U.S. president and Marcos that resulted in an un-reciprocal imbalance of a 0% to 19% U.S. to Philippine tariff imposition. Never mind that such would likely ravage the export-import factor that comprises our gross domestic productivity formula.

Four other issues that should have been addressed as they were headlined by media failed to be in what seemed as an eleventh-hour haphazardly crafted SONA.

One, the shift from Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators or POGO to Philippine Internet Gaming Operators or PIGO by Marcos’s economic team raises significant concerns. While the previous POGO framework fostered criminal activity and corruption at the local government level, the new PIGO model exacerbates issues related to the financial well-being of Filipino families. Add to these attendant illegal operations such as human trafficking, drug havens, modern day slavery and the creation of criminal enclaves, collectively worsening the deterioration of traditional values Filipinos once held.

Two, the imposition of a 20% tax on interest earnings from deposits cleverly guised in legislation that focuses on the development of the capital markets rather than on savings and frugality is counterproductive, particularly for the middle and CDE classes. This policy discourages savings, as effective returns on deposits diminish, potentially leading individuals to seek alternative risk-prone investments. While promoting the channeling of disposable incomes to a market that is prone to insider trading and stock manipulation especially for low capital issues, the resulting reduction in strictly regulated bank deposits ultimately weakens the banking sector and limits available capital for investments in the economy.

Three, the restructuring of the Energy Regulatory Commission, the energy watchdog of the power sectors that is responsible for high headline inflation and the highest electricity rates among Asia amid concerns of conflict of interest is troubling. The appointment of non-technocrats and conflicted individuals with private sector ties raises questions about the impartiality and effectiveness of the regulatory body. Given that foreign direct investment is sensitive to operational costs, including unreasonable or overcharged electricity prices, the lack of transparency and potential for bias in this reorganization deters much-needed investments needed to reduce costs of doing business in the Philippines.

Four, the virtual resurrection and reenactment of the inequitable and predatory provisions of the Bell Trade Act and Laurel Langley Agreement significantly and quite negatively impacts on our natural resources and patrimony. While fostering ties with the U.S. is beneficial, offering parity to American companies guised in the details of the 0% to 19% tariff cop-out seriously undermines local interests and limits the Philippines’ control over its own resources. This creates economic dependency that hampers national sovereignty and benefits primarily foreign interests.

These handful of issues illustrate a pattern of self-inflicted wounds within the government’s policy decisions that have long-term detrimental effects on the country’s socio-economic stability. They raise critical questions regarding the governing bodies’ ability to effectively assess the implications of their policies and to prioritize Filipino interests.

Effective governance requires adaptive strategies that consider long-term impacts, stakeholder interests, and the prevention of economic disparity. The concern is not only about individual policies but importantly about the coherence and sustainability of the haphazard directions undertaken by Marcos’s economic team of presidential whisperers.

Dean de la Paz is a former investment banker and a managing director of a New Jersey-based power company operating in the Philippines. He is the chairman of the board of a renewable energy company and is a retired Business Policy, Finance and Mathematics professor.