By Giff Johnson

For Variety

MAJURO — Although evidence shows that the entire Marshall Islands was subjected to radioactive fallout from hydrogen bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the 1950s, there are three specific populations who were exposed to relatively high levels of radiation by United States government actions from the 1950s to the 1970s — and for whom there has never been any type of medical monitoring or follow up.

People in Marshall Islands often make the claim, with some justification, that the entire country, every atoll and island, was exposed to fallout from the 67 nuclear tests conducted from 1946 to 1958. A once secret U.S> Atomic Energy Commission report, issued in classified form in 1955 following the 1954 Operation Castle series of hydrogen bomb tests at Bikini, lists external exposures recorded on virtually every inhabited atoll and island in the Marshall Islands. This AEC report confirms the widespread nature of hydrogen bomb test fallout throughout this country, contrary to U.S. government claims over decades that only a few islands in the northern part of the country were contaminated.

On one hand, the U.S. government has, since 1954, operated a special medical program for the 82 people from Rongelap Atoll and 157 Utrok Atoll people who were living on their home atolls on March 1, 1954 and heavily exposed to Bravo hydrogen bomb test fallout. Today, over 70 years after Bravo, there are only a handful of originally exposed Rongelap and Utrok people still alive and the U.S.-funded medical program will end at some point in the not-too-distant future.

On the other hand, there has been scant focus on several specific groups of Marshallese who were exposed to high levels of radiation — put in harm’s way — by actions and policies of the U.S. government.

The special medical program for those exposed to Bravo test fallout in 1954 on Rongelap and Utrok begs the question, why is there no medical follow up for other groups in the Marshall Islands? For example:

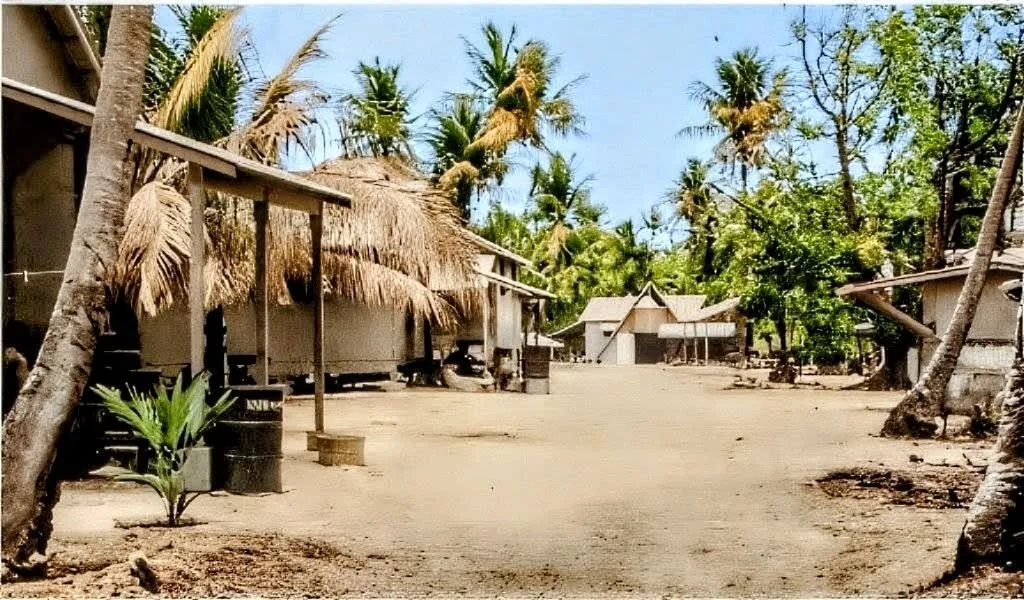

• The 139 Bikini people who returned to Bikini Atoll in the early 1970s after U.S. authorities declared the former nuclear test site safe for habitation, built houses for them on Bikini and assisted with their repatriation home. Because the Bikinians were evacuated in 1946, they were not subjected to large doses of radioactive fallout from Bravo and other hydrogen bomb tests in contrast to others living in the northern Marshall Islands.

The 139 Bikinians allowed to return home by the U.S. government become the first seriously radiation-affected Bikini population.

As early as 1975, barely three years into their return to Bikini, warning signs were appearing about radiation safety, with an Interior Department official quoted at the time as saying it “appears to be hotter or questionable as to safety.” That same year, an Atomic Energy Commission report on Bikini suggested that some ground wells were too radioactive for safe use, and consumption of pandanus, breadfruit and coconut crabs needed to be prohibited. Still, the 139 Bikinians remained on the island, unaware of the increasing awareness of U.S. scientists about the hazards of living on Bikini.

In June 1977, a report by the Department of Energy (successor agency to the Atomic Energy Commission) said: “All living patterns involving Bikini Island exceed Federal (radiation) guidelines for 30-year population doses.” Still, the group remained there, ingesting or breathing in radioactivity daily.

A Lawrence Livermore Laboratory study on Bikini in 1977 was blunt about how scientists viewed Bikinians living on Bikini: “Bikini may be the only global source of data on humans where intake via ingestion is thought to contribute the major fraction of plutonium body burden…it is possibly the best available source of data for evaluating the transfer of plutonium across the gut wall after being incorporated into biological systems.”

“Biological systems” being, of course, a reference to human beings.

By May 1978, U.S. authorities reported that studies of the Bikinians living on Bikini showed a 75% increase in body levels of Cesium 137 and announced plans to evacuate them. That evacuation took place in September 1978. From that time until today there has never been any special medical monitoring or attention paid to this group of 139 Bikinians who by virtue of U.S. government assurances of the safety of the atoll were subjected to six years of radiation exposure.

Ultimately, the 139 people were evacuated in 1978 to Ejit Island in Majuro by U.S. authorities after they ingested high radiation levels from living in a seriously contaminated environment.

• The over 200 Rongelap Islanders who had not been on Rongelap Atoll during the Bravo test in 1954 but were moved back to Rongelap in 1957 along with originally exposed people as a “control group” for ongoing radiation studies by the U.S. Brookhaven National Laboratory. This group of 200 may have received some radioactive fallout from Bravo living on other islands in the Marshalls, but it was minuscule compared the 82 originally exposed Rongelap people who were engulfed in Bravo’s snowstorm of radioactive fallout on March 1, 1954.

The statement in a Brookhaven National Laboratory report about the return in 1957 showed both that Rongelap was the most radiation-contaminated place in the world where people were living and revealed the intent of the doctors with the control group: “Even though the radioactive contamination of Rongelap Island is considered perfectly safe for human habitation, the levels of activity are higher than those found in other inhabited locations in the world,” said the Brookhaven report. “The habitation of these people on the island will afford most valuable ecological data on human beings.”

Brookhaven called the “control” group “an ideal comparison population for the studies.”

More than a year later, Brookhaven doctors reported that the levels of radiation in the bodies of the people who returned in 1957 skyrocketed from absorbing Bravo fallout in the Rongelap environment, which had not been cleaned up prior to the 1957 return. In just one year, Brookhaven follow up medical examinations showed that Rongelap Islanders’ body levels of Cesium 137 rose 60-fold, Strontium 90 rose 20-fold, and Zinc rose eight-fold from living on Rongelap.

Yet while the U.S. government has maintained a special medical program from 1954 to this day for the original 82 exposed Rongelap Islanders, there has never been an ongoing and systematic medical program to check and treat the 200 people who had not been on Rongelap in 1954 but were allowed by the U.S. government to return to live in 1957 to a highly radioactive environment.

• The 400 inhabitants of Ailuk Atoll, who U.S. authorities acknowledged at the time of the Bravo test received a dose of radioactive fallout similar to the Utrok people — but said it was too much of a logistical problem to evacuate them due to the population size. Utrok, with a smaller population, was evacuated after Bravo.

A U.S. government report at the time noted that the “only other populated atoll which received fallout of any consequence at all was Ailuk…Balancing the effort required to move the 400 inhabitants against the fact that such a dose would not be a medical problem, it was decided not to evacuate the atoll.”

In fact it was true that both Ailuk and Utrok had relatively low exposures compared to the high dose experienced by the Rongelap people. Significantly, the claim by U.S. officials in 1954 that Ailuk’s exposure “would not be a medical problem” was based on nothing because at the time, little was known about the long-term health effects of radiation. Moreover, this baseless claim was debunked by the experience of the Utrok people 22 years after Bravo.

In 1976, Utrok, whose dose was calculated at about one-twelfth of Rongelap’s, suddenly showed a higher rate of thyroid cancer than the Rongelap people — a development that made headlines in the Los Angeles Times. This finding by Brookhaven National Laboratory indicated both the long latency period before health problems develop after exposure and the significant risk of what was assumed to be a low dose exposure.

As with the 139 Bikinians and the 200 Rongelap Islanders — mentioned above — there has never been any systematic medical follow up with the 400 originally exposed Ailuk people.

These are forgotten victims of the U.S. nuclear test legacy who were exposed to radiation by decisions of the U.S. government.