HUMAN trafficking is the greatest crime of the modern world, and China is on the front lines, but not in a good way. China is one of the largest suppliers of slaves while also one of the largest consumers of them. A shocking case has brought China’s trafficking problem into the spotlight, just as the world is glued to the Olympic games in Beijing. Bad timing, or deliberate timing? You decide.

Two weeks ago, video surfaced showing a middle-aged woman with a chain around her neck. Her clothes were modest, even though she stood in a filthy shack with no door in the dead of winter. Chinese media originally identified her by name, Miss Yang, mother of eight, and said she had mental health problems.

Soon the story unraveled as questions outnumbered answers, and it was clear the media either did not do their job, or they were complicit in a coverup. Further reports identified her as Xiaohuamei, which means Little Plum Blossom, not a normal name for a Chinese but possibly a nickname. Many people commented that she bore a striking resemblance to another Chinese woman who went missing twenty years ago. Could they be the same?

What about those eight children? Everyone is familiar with China’s One Child policy, now expanded to two children. In a tightly controlled state such as China, where registry and paperwork are practically a religion, how could that be? Did they attend school under false names? Where are they now? Did the couple sell their children to others, making them traffickers themselves? Was the woman imprisoned as a baby factory for someone else’s profit? If the children are alive and living normal lives, why haven’t they come forward in defense of their mother?

What about the chain around the woman’s neck and her cruel surroundings? Does mental illness justify such treatment? The poor woman is treated in a way that would outrage animal rights activists. If she has mental illness, why isn’t she in a state facility getting help instead of locked up in chains? Perhaps she is chained because she is being kept illegally and would run to the police.

Xiaohuamei has become a focal point for Chinese who are tired of state propaganda and media obfuscation. Web bloggers and hashtaggers have taken up the cause, seeing this as a clear case of human trafficking. Even if the woman is legally married, which the media claims, how can her treatment be excused, or worse, justified? The Chinese legal system does not recognize rape within a marriage, a fact that women’s rights groups are fighting to change.

Another twist to this story emerged when the public was informed that the woman had been married before and lived in another province two thousand miles away. We were told that she had been brought to her current location by a friend who was to find a mate for her and possibly get help for her mental illness. So, was she sold? Paying for a bride was made illegal in China only in 2015, and the maximum punishment is three years in prison. Who was the friend? The Chinese people want to know if any of this can be verified, or if this is just another media smoke screen.

Representative of the kinds of questions asked by Chinese bloggers is this: “How old is Xiaohuamei? Does illegally imprisoning a mentally-ill person and having sex with her constitute rape? Who approved her fake household registration, her national ID, her children’s birth permits and household registrations? Should they be held accountable? Please answer. Thank you.”

There is clearly more going on here than we have been told, and the story changes with every media update. As one who is deeply concerned for human rights and the plague of trafficking, I will follow this story as it develops. Perhaps justice can be done for this woman.

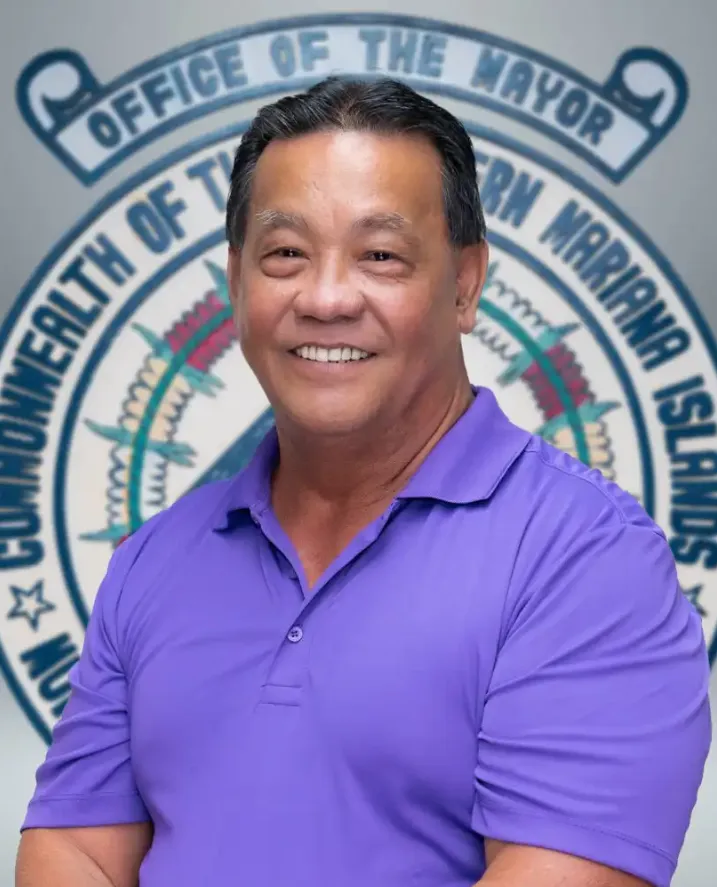

BC Cook, PhD lived on Saipan and has taught history for 20 years. He currently resides on the mainland U.S.

BC Cook